With increasing prosperity, ration cards have lost their meaning. But it wasn’t so always. In earlier times, the loss of a ration card meant the loss of a loved one. Kashmir Scan explores the history of this important document which is on the verge of becoming obsolete.

By Ajaz Rashid

Historian and satirist Zareef Ahmad Zareef vividly remembers the time when the people of Kashmir used to collect firewood from the government stores in Kashmir by producing ration cards. It was a time of abject penury in Kashmir when food was scarce, and the electricity supply was a dream.

“For any Kashmiri, a ration card was as precious as a State Subject Certificate. If a family were to lose their ration card, it was as if they had lost their loved one,” Zareef said.

According to historians, the ration cards, which are issued in the name of the family head, typically the male member, were introduced around 1926 when Dogra king Maharaja Hari Singh ruled the then princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Since J&K was reeling under acute food scarcity, it prompted Maharaja Hari Singh to issue ration cards, preceded by the grant of State Subject Certificates to locals. With these two decisions, the Maharaja killed two birds with one arrow; locals of J&K were guaranteed protection of their personal assets, including land and other immovable properties, and also a fixed quota of food items, even though it was meagre, as well as firewood, while as the non-locals, who might have thought about settling in Jammu and Kashmir, was assured of a struggle even for a morsel in the absence of ration card.

According to historians, the ration cards were introduced around 1926 when Dogra king Maharaja Hari Singh ruled the then princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

In the initial days, people living in the villages and far-flung areas of Jammu and Kashmir, most of whom grew their own rice, didn’t require ration cards, while those living in Srinagar got their monthly allocation of rice grains, firewood, and wheat only when had ration cards issued by the Dogra government.

“The Maharaja forced the farmers to pay up ‘mujwaz’ (a portion of harvested food grains) in the form of wheat towards the state, which was then distributed to people mostly in the form of flour. Since there was a lot of food scarcity, one family member used to get around 100 gm of food grains per day which was not sufficient,” Zareef said.

After the independence in 1947, a major change took place in 1953 when the National Conference founder Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, who had exhorted people to eat roasted potatoes to defeat the pangs of hunger till J&K became self-sufficient in food production, was thrown into jail and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad took over the government.

The Food Corporation of India took over and introduced the Public Distribution System (PDS) for systematic distribution of food and non-food items, “Rice grains were sold for eight annas per kilo, but most of the grains were rotten, which compounded the problems of Kashmiris who were facing acute shortage of food. With the advent of time, the government also started distributing kerosene and sugar at ration shops. When Sheikh was released from jail, he even promised to provide cloth to people at ration shops,” Zareef said.

A senior official in the Department of Food, Civil Supplies, and Consumers’ Affairs said about 6,738 fair price shops in Jammu and Kashmir, also known as ration depots. “A supervisor from the department is entrusted with the job of overseeing the process of distribution of food and non-food items like rice, sugar, flour, and kerosene,” the official said.

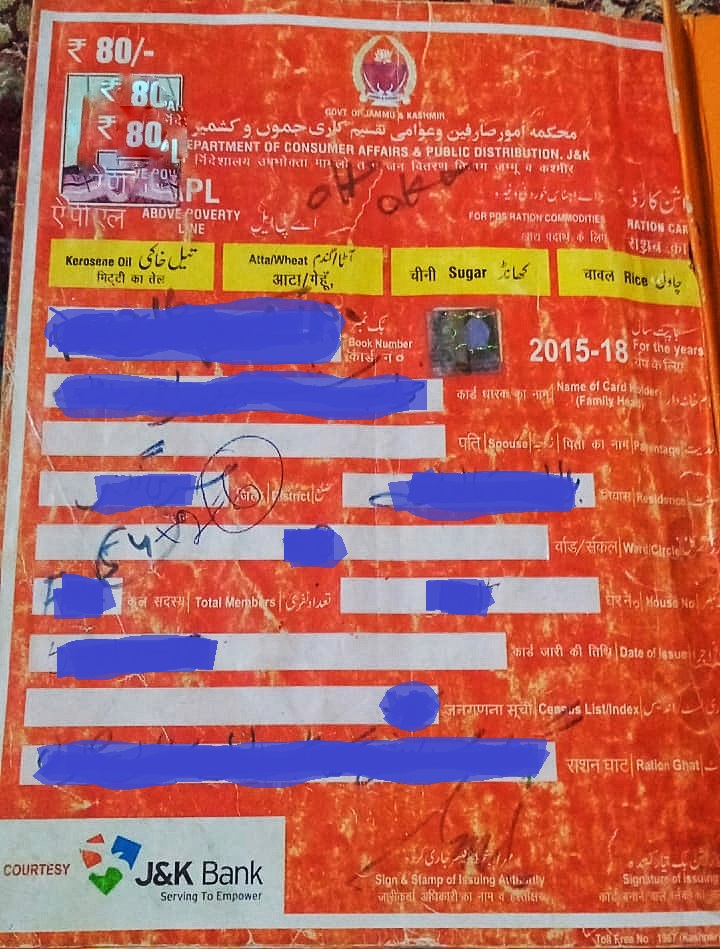

In 1997, the J&K government launched ‘Targeted PDS’ (TPDS), which catered to economically downtrodden people. Under TPDS, beneficiaries were divided into ‘Below Poverty Line (BPL) and ‘Above Poverty Line (APL) categories. In 2016, under the PDP-BJP coalition government, J&K was brought under the ambit of the National Food Security Act, 2013, under which food and non-food items are given to several categories of people under various schemes such as Annapurna Yojna, Antyodaya Yojna, and Priority Household, besides APL and BPL.

With the trajectory of the human development index showing visible indicators of improvement across the country as well as J&K, the ration card has become redundant, if not completely obsolete.

With the increasing population putting an extra burden on the distribution process and opening up opportunities for the manipulation of data, many media outlets reported that there was leakage in the distribution of food and non-food items at ration depots in not just Jammu and Kashmir but across the country. There were also allegations that some well-off families had managed to get BPL cards, making them undue beneficiaries of welfare schemes in the form of subsidised food and non-food items, which are essentially meant for J&K’s poor.

To put an end to this fraud, the Centre, as well as J&K government, started digitising the food distribution system by linking the Aadhaar number of the beneficiaries to their ration cards. The loopholes were significantly plugged with ration cards linked with Aadhaar, which identifies a beneficiary through two indicators of fingerprints and iris reflection. According to reports, 4.39 crore forged ration card holders were struck off the list in the country, with more than two lakhs in Jammu and Kashmir alone.

However, with the Aadhaar-based identification requiring confirmation of the beneficiaries every month, it has become problematic and a source of grave inconvenience, especially for the elderly and women. The problem is also compounded by erratic internet connectivity and power disruption, which means a loss of precious time and effort for those who want to collect their monthly quota of rice and other food and non-food items.

Today, with the trajectory of the human development index showing visible indicators of improvement across the country as well as Jammu and Kashmir, the ration card has become a redundant, if not completely obsolete, document, especially for the rich and the upper-middle class who prefer to stock Kashmiri or Basmati rice, instead of standing in queues outside the government-run ration depots.

“Prosperity has opened many windows of opportunities. With money in their pockets, people can buy whatever they would like to eat. Instead of the monthly allocation of the rice grain, we get a monthly quota of medicine for pharmacies now,” quips Zareef.

Leave a Reply