Before it could educate, ‘Phule’ is being rewritten. Who decides what India can remember?

By Kalpana Pandey

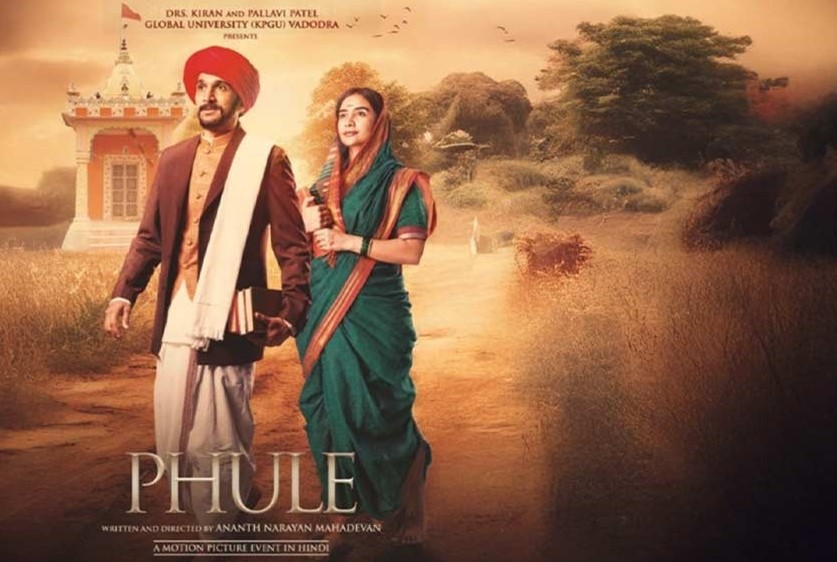

“Phule,” a forthcoming biographical film directed by acclaimed National Award–winning filmmaker Ananth Mahadevan—known for his sensitive and thought-provoking works like The Storyteller—has become the focal point of a major controversy even before its theatrical release. The film, which explores the life and legacy of two of India’s most visionary social reformers, Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule, was originally scheduled for release on April 11, 2025. This date was not chosen at random; it marks the birth anniversary of Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, a symbolic choice intended to underscore the enduring relevance of his work. However, due to objections raised by certain Brahmin organizations in Maharashtra, the film’s release has now been postponed to April 25. These groups have accused the film of promoting caste-based animosity and misrepresenting their community, igniting a storm of debate over censorship, historical truth, and the boundaries of artistic freedom.

At the heart of “Phule” lies a dramatization of the pioneering efforts undertaken by Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule in the mid-nineteenth century. As the founders of India’s first school for girls in 1848 and relentless campaigners against caste and gender discrimination, the Phules occupy a central place in the pantheon of India’s reformist thinkers. The film seeks to bring their crusade to life on the screen, documenting their groundbreaking educational and social initiatives, their resistance to Brahminical orthodoxy, and their unwavering commitment to the upliftment of the so-called “lower castes” and oppressed communities. Pratik Gandhi stars as Jyotirao Phule, with Patralekha portraying Savitribai, together anchoring a narrative that seeks not only to inform but also to inspire a new generation to reflect on the unfinished project of social justice.

However, instead of being celebrated as a long-overdue tribute to two of India’s most important change-makers, the film has become entangled in a complex web of political, cultural, and bureaucratic challenges. Following complaints from right-wing Brahmin groups who allege that the film paints their community in a negative light, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has recommended a series of controversial edits. These include the removal or alteration of historically accurate caste-specific terms such as “Mang,” “Mahar,” and “Peshwai,” as well as the substitution of a line referring to “three thousand years of slavery” with the more ambiguous and sanitized phrase, “many years of slavery.” Such revisions, critics argue, not only dilute the historical realities the film seeks to confront but also compromise the ideological core of the Phules’ radical message.

The controversy surrounding “Phule” raises profound and urgent questions about the CBFC’s consistency and fairness in applying its certification standards. In recent years, other films—most notably The Kerala Story and The Kashmir Files—were cleared for release despite their polarizing content and the significant public outcry they provoked. These films, which advanced particular ideological narratives and contained incendiary statements, were allowed to proceed without major censorship, suggesting a certain ideological leniency. In stark contrast, a film like “Phule,” which champions the cause of equality, education, and justice, and which is rooted in well-documented historical facts, is being subjected to a litany of restrictions and delays. This inconsistency invites serious scrutiny. It suggests that the CBFC’s decisions are influenced less by objective criteria and more by the political and social power dynamics at play. When films that confront caste oppression and expose historical inequities are censored under the pretext of maintaining social harmony, while other films with divisive agendas are waved through, the board’s impartiality becomes highly suspect.

Moreover, the caste question in India is not a relic of the past; it continues to be a living, burning issue that affects millions of lives. Despite constitutional protections, discrimination on the basis of caste remains entrenched in everyday life—manifesting in access to education, employment opportunities, religious practices, and even basic human dignity. In this context, a film like “Phule” serves not merely as historical documentation but as a mirror to present-day realities. It challenges viewers to reckon with the enduring legacy of caste hierarchies and to question why those who seek to confront these truths are so often silenced. The resistance faced by the film is therefore emblematic of a larger discomfort with confronting the structural violence that has shaped Indian society.

The CBFC’s actions also reveal a troubling hierarchy in how public sentiment is weighed. The objections from Brahmin organizations were met with swift and serious consideration, resulting in significant alterations to the film. Yet the filmmakers have repeatedly emphasized that the film does not seek to vilify any community. On the contrary, it includes sympathetic portrayals of Brahmin individuals who supported the Phules’ reformist mission. The film’s intention is not to incite hatred but to reflect the historical context in which the Phules lived and fought. However, these clarifications appear to have had little impact. By prioritizing the grievances of certain caste groups over the filmmaker’s artistic integrity and historical accuracy, the CBFC has sent a chilling message—that artistic narratives must defer to political sensitivities, even when those sensitivities conflict with the truth.

This deference is especially problematic given the philosophical and political nature of the Phules’ work. Jyotirao Phule was not merely a reformer; he was a revolutionary who directly challenged the Brahminical order. He and Savitribai were ostracized by their own communities, faced relentless social and religious backlash, and were branded as atheists and enemies of tradition. Yet, they persisted. Their work laid the foundation for a broader movement for equality that would later inspire giants like Shahu Maharaj, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, and Periyar. In their schools, children from Dalit, Shudra, and other marginalized communities were welcomed without discrimination. Caste was never asked—an idea that was nothing short of revolutionary at the time. Through their writings, particularly Gulamgiri (“Slavery”), the Phules laid bare the exploitative nature of caste and religious orthodoxy. Their radical declaration—“God is not the creator of man; man is the creator of God”—was a direct challenge to religious and social hierarchies that privileged a few at the expense of the many.

The film Phule thus seeks to portray this legacy in all its courage, clarity, and controversy. It is not a comfortable film, nor should it be. Its strength lies in its unflinching commitment to telling a story that has too often been sanitized or ignored in mainstream discourse. Yet, by demanding cuts that soften the film’s critique, the CBFC is in effect demanding that history itself be rewritten to suit the tastes of the dominant class. Such censorship represents not only a threat to artistic freedom but a betrayal of the democratic principles that allow for dissent and debate.

Director Ananth Mahadevan has defended his work unequivocally, stating that his intention is not to provoke or incite but to educate and inspire. The film, he asserts, is a cinematic homage to two figures who fundamentally reshaped Indian society and offered a vision of inclusive progress. However, in a socio-political climate increasingly hostile to voices of critique and challenge, even the act of education can be seen as subversion. This reality underscores the larger battle being waged—not just on the screen, but in the public imagination and in the institutions that claim to protect artistic expression.

Whether or not Phule ultimately reaches audiences in its unaltered form, its existence already serves a crucial purpose. It has re-opened vital conversations about caste, censorship, and the politics of memory. It forces us to ask: Who gets to tell our history? Whose version of the past is allowed to prevail? And how long will we allow truth to be compromised in the name of comfort?

The Phules’ legacy is not confined to textbooks or commemorative plaques. It lives on in every effort to democratize education, in every challenge to social stratification, and in every demand for justice. The struggle they began is not over—it continues, often invisibly, often painfully, in homes, classrooms, courts, and now, cinema halls. The film Phule is not merely about two reformers from the nineteenth century. It is about India itself—its past, its present, and the future it chooses to create.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at [email protected]

Leave a Reply