Walraman is not just a village with a mysterious name; it is a place where legends thrive, spirituality is deeply ingrained, and communal bonds are strengthened through shared rituals and beliefs.

By Hilal Ahmad Tantray

Walraman, a quaint village located in Baramulla district, lies approximately 13 kilometers away from the district headquarters. Despite its serene presence, the origin of its name remains shrouded in mystery, with no written records to explain why it’s called Walraman. However, the village is steeped in legends. According to an elderly resident, the name might derive from ‘Wular,’ inspired by a stream that once connected to Wular Lake. Some believe the name has Hindu origins, suggesting that the village was named after a Hindu resident named ‘Raman,’ who once lived in the area.

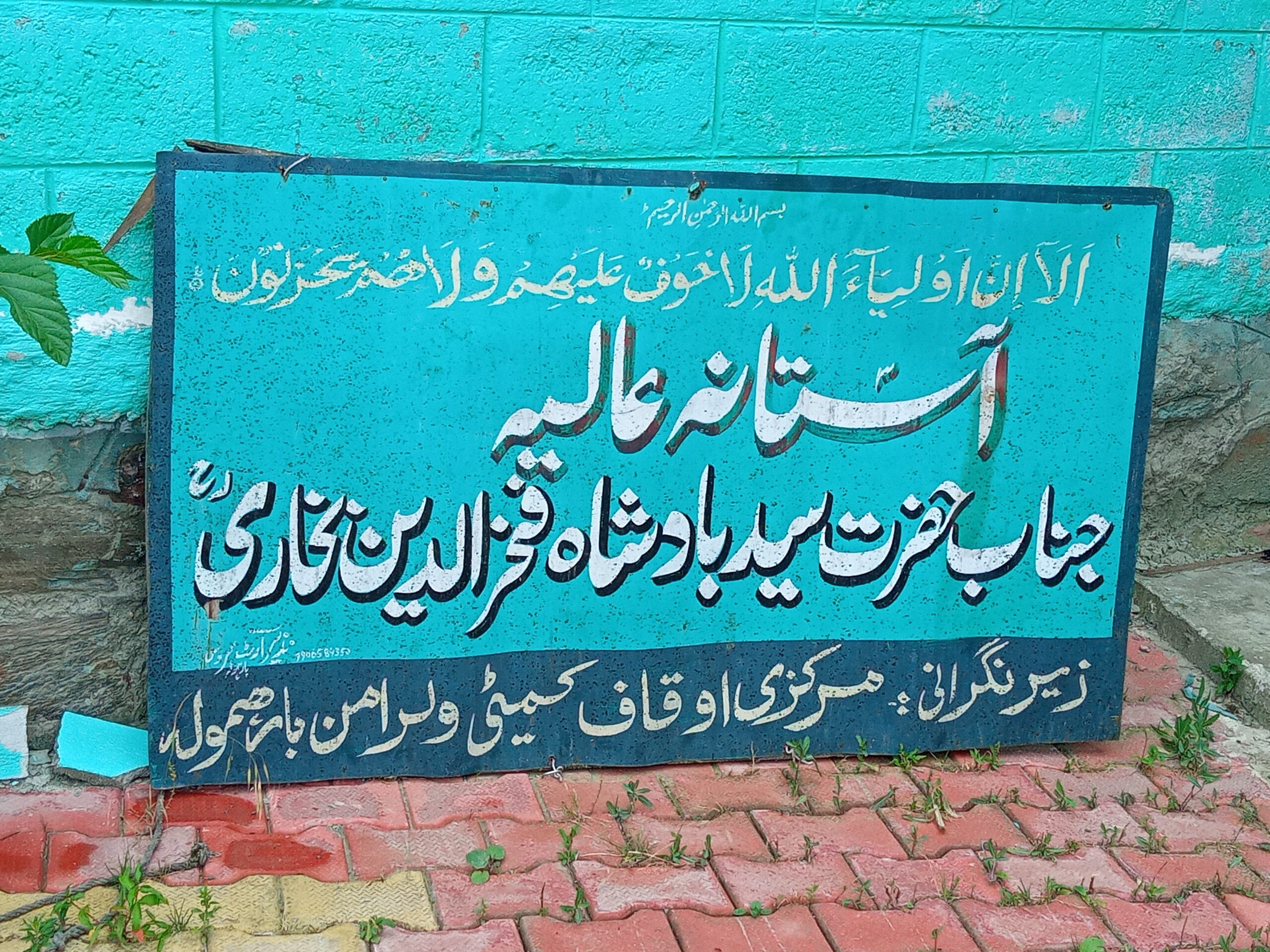

Kashmir, often referred to as “pir waer,” meaning “the valley of saints,” is a region where spirituality profoundly influences the land and its people. The valley is dotted with numerous Sufi shrines, and Walraman is home to one such sacred spot: the shrine of Syed Fakhruddin BukhariRA, locally known as ‘Sead Soab.’ This revered saint from Central Asia is believed to have stayed in Walraman for some time before moving to other places due to a shortage of water. His shrine attracts many visitors, especially on Friday mornings, who come seeking blessings and praying for their wishes. Devotees often bring food offerings like bread, wheat, and rice to feed the birds near the shrine, symbolizing their wishes for the well-being of humanity. Those facing health issues visit the shrine, hoping for divine intervention and recovery.

The communal rituals at the shrine foster a sense of unity and shared hopes among the villagers. When an individual is severely unwell, a customary practice involves making a serious pledge or vow at the shrine on behalf of the afflicted person, seeking their well-being. This commitment often entails offering animals such as sheep, goats, and hens, and sometimes other items. The cooked food from these offerings is then shared within the community. In certain instances, villagers perform a ritualistic slaughter of these animals, and the meat is divided among the people, a practice known as “thapi thapi” in Kashmiri. This tradition is deeply rooted in the belief that such actions will contribute to the ailing individual’s recovery. The villagers are convinced that by making these offerings and performing ritualistic acts, they establish a spiritual connection, channeling positive energy toward the sick person’s well-being. The shared communal experience reinforces the collective belief in the healing power of these traditions.

Moreover, this belief system extends to a specific ritual involving the preparation of ‘Taeher,’ a mixture of rice, turmeric, and mustard oil. Crafted when someone experiences fear in a dream, ‘Taeher’ is offered at the shrine, further emphasizing the interconnectedness of spiritual practices with the conviction that these rituals can influence the course of an individual’s health. Despite its traditional nature, this belief system persists, highlighting the enduring faith in the efficacy of these customs for the betterment of those facing health challenges.

Another interesting aspect is the practice known as ‘Bhandar,’ meaning the assembly of people, which the Kashmiri people refer to as ‘Bhandar.’ Whenever there are natural calamities like heavy rain or drought in the village, prominent members of the community, such as the Masjid committee or Darsgha committee, locally known as ‘Zeath,’ collect items like money, rice, etc. These collected items are then presented in front of a sacred place called ‘Asthan’ as an offering. For this purpose, someone knowledgeable in the village, either a Quran reader or someone with spiritual understanding, sits and recites the ‘Khatam e Sharif’ or ‘Khatam e Quran.’ This place is accompanied by a graveyard that people often visit on significant days like ‘Laylat ul-Qadr,’ ‘Shab-e-Barat,’ and ‘Eid.’ On these special days, people gather to engage in morning Fajr prayers, offering supplications for the forgiveness of the departed. Additionally, a unique tradition involves each family bringing food to this place, fostering a sense of communal sharing and unity during Eid-ul-Fitr or Eid-ul-Adha. After the prayers, individuals partake in meals together, creating a meaningful and shared experience among the community.

One more fascinating tradition is observed if someone is getting married during the rainy season. They bring a stone from this shrine, place it into the fading flames of the mud hearth, locally known as ‘Dambur’ (Daan), so that it doesn’t rain on the wedding day. On the wedding day, when preparing the meal, the first plate (Batt treem) is placed on this shrine, with each variety of meat decorating this special plate. After that, the meal is divided among the guests. Similarly, when the bridegroom goes to bring his wife, he must first visit this pilgrimage site, pray, and then proceed to bring his wife. This tradition is still followed today.

In the context provided, when someone secures a job in a household, a ritual is performed by tying a piece of green cloth, known as ‘Deach,’ at a particular shrine. This act is likely a symbolic expression of gratitude or seeking blessings for the newfound employment. Similarly, if someone brings a car to the village, a customary offering or act of devotion, referred to as ‘Niyaz,‘ is performed. This could involve making a donation or providing something of value as a gesture of appreciation or celebration for the arrival of the vehicle. These practices blend cultural and religious elements, reflecting traditions associated with expressing joy or seeking divine favor in response to significant events like job opportunities or the acquisition of a new asset.

If a household’s cow gives birth to a calf, they collect its milk for 5-7 days, improve its condition, and then divide the cheese, locally known as ‘Tchaman,’ among the neighbors. Then, they take some milk, rice, and bread to this shrine site, mix them, and offer it. They also light candles, locally called ‘Tchounge.’

The monthly income of this shrine ranges from eight to ten thousand, collected by the Auqaf committee every month. There is a drum fixed in a financing wall of this place where people deposit rice, and the money obtained by selling that rice is used for the benefit of this place. This money is utilized for the upkeep of the shrine. Sayid Fakhr ud Din Bukhari’s shrine is considered a place of ‘garm ziyarat’ or fervent pilgrimage because, for instance, if someone makes a promise or borrows money from someone else, they take them to his shrine to make them swear. If they lie, they are deemed to be punished divinely.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at [email protected]

Leave a Reply