Witness the ticking time bombs of transient ischemic attacks, revealing crucial clues to imminent cerebral infarction. Stay vigilant, stay informed.

By DR. T. Vishnu Murthy

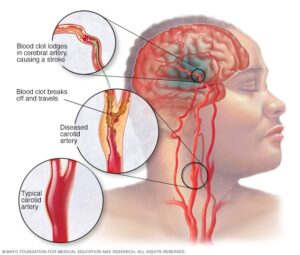

Cerebral vascular diseases manifest in two primary categories: those leading to ischemic cerebral infarction and those culminating in intracranial hemorrhage. The incidence rates of distinct types of cerebral vascular accidents or strokes vary.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS IN CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE:

The brain receives blood supply from four major arteries: the two common carotids and the two vertebrals. One common carotid artery originates from the aortic arch, while the other arises from the innominate artery in the upper thorax. The two vertebral arteries stem from the right and left subclavian artery. Within the neck, the common carotid artery bifurcates, giving rise to the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal carotid artery enters the skull through the ipsilateral foramen lacerum, traverses the cavernous sinus, and branches out in the following sequence:

- Ophthalmic,

- Anterior choroidal,

- Posterior communicating.

Subsequently, it divides into the anterior and middle cerebral arteries.

The Anterior Cerebral Artery:

The anterior cerebral artery supplies blood to the medial and superior surfaces of the cerebral hemisphere and the foremost portion of the frontal lobes. This region encompasses the motor and sensory cortex for the foot and leg, along with the supplementary motor cortex. Additionally, the anterior cerebral artery provides blood to vital deep structures, including the anterior nucleus of the thalamus and a segment of the anterior limb of the internal capsule.

The Middle Cerebral Artery:

The middle cerebral artery nourishes the lateral surface of the cerebral hemisphere, excluding the occipital and frontal poles. It encompasses the primary motor and sensory areas for the face, hand, and arm, as well as the optic radiations. In the dominant hemisphere, it also encompasses cortical areas pertinent to speech. Perforating branches of the middle cerebral artery extend to the core of the cerebral hemisphere, supplying the internal capsule and basal ganglia.

The Posterior Cerebral Artery:

The posterior cerebral artery provides blood to the posterior pole of the lateral cerebral hemisphere, the posterior segment of the cerebral hemisphere, and the posterior part of the medial and inferior surfaces of the hemispheres. This region includes the calcarine cortex, the primary visual receptive area. Short perforating branches of the posterior cerebral artery supply the thalamus, a portion of the optic pathways, and other diencephalic structures, including the midbrain.

STROKE SYNDROMES:

An adequate understanding of the symptoms and signs of cerebrovascular disease necessitates classification of the diverse clinical entities constituting the stroke syndrome.

Cerebrovascular accidents are categorized based on the anatomic site of ischemia or infarction, the cerebral vessels affected, and the temporal characteristics of the entire clinical episode. The latter is particularly clinically significant, as therapy often varies depending on the temporal profile. Three kinds of temporal profiles are typically encountered:

- a) Cerebral Transient Ischemic Attacks b) Stroke-in-Evolution c) Cerebral Infarction

Read Also: CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES—HEART FAILURE

CEREBRAL TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACKS

The symptoms exhibit variability, contingent upon the ischemic area of the brain, presenting two primary types: those associated with ischemia affecting portions or the entirety of a cerebral hemisphere, and those linked to brainstem ischemia. Predominantly, symptoms entail transient contralateral weakness in facial, digital, manual, or limb muscles. Additionally, patients might experience fleeting sensory manifestations such as tingling, pins and needles sensation, or numbness contralateral to the ischemic region. Ischemia affecting the dominant hemisphere may induce dysphasia, characterized by speech impairment and, at times, transient comprehension deficits.

Individuals with ischemia localized in the posterior cerebral artery-supplied brain region may encounter symptoms like blurred vision or transient occurrences of hemianopic or altitudinal visual field defects, along with visual activity impairment. Ischemia or insufficiency stemming from internal carotid artery stenosis often triggers transient retinal ischemia, leading to monocular blindness or reduced acuity on the stenosis-afflicted side, concomitant with contralateral facial, arm, or leg weakness.

Episodes of ischemic attacks may manifest multiple times daily or intermittently over weeks or months, even spanning several years. Some patients enduring internal carotid artery occlusion may undergo transient ischemic attacks persistently for up to two years before succumbing to cerebral infarction. The paramount significance of transient ischemic attacks lies in their indication of substantial cerebrovascular pathology, explicitly signaling the looming threat of cerebral infarction.

Between transient ischemic attacks, neurological examinations typically reveal normalcy. During an attack, patients frequently exhibit corresponding deficits, such as hemiparesis, reflex asymmetry, extensor plantar response, mild hemisensory or visual field deficits, or dysphasia if the dominant hemisphere is affected. Brainstem ischemic attack evaluations may unveil nystagmus, complete facial, palate, and tongue weakness, dysconjugate eye movements, sensory defects, and unilateral or bilateral body-side weakness. Examination must include meticulous inspection of the optic fundus through a dilated pupil to detect cholesterol or platelet emboli in the arterial tree, crucial in identifying embolic sources in the carotid artery.

STROKE IN EVOLUTION

The evolving stroke is marked by gradual paralysis and sensory impairment spanning hours, occasionally extending to one to two days. Symptoms may evolve in a series of step-like progressions or as a continuous deterioration. Initially, patients may exhibit mild weakness, escalating over hours to involve larger body areas. The symptomatic profile mirrors that of a completed stroke, differing only in the time frame of onset. A similar progression can be observed in subdural hematoma and brain tumors, albeit typically over several days or weeks.

CEREBRAL INFARCTION

Cerebral infarction resulting from cerebral emboli or atherosclerosis and thrombosis cannot be distinguished solely by the neurological manifestations they induce. However, disparities exist in symptom onset and general physical evaluation.

Cerebral embolism prompts an abrupt symptom onset, often preceded by headaches several hours prior. In contrast, infarctions due to atherosclerotic vascular occlusion or stenosis typically entail a less sudden onset. Neurological symptoms may progress steadily or be preceded by transient ischemic attacks, reflecting a gradual symptom onset akin to stroke evolution. Although rare, a gradual onset over days or occasionally a week can occur. Infarctions limited to the cerebral hemisphere may evoke weakness or paralysis contralateral to the affected region, accompanied by impaired sensory perception and complaints of arm or leg heaviness or numbness. Visual field defects are common but may elude patient notice. Brainstem infarctions manifest an array of symptoms including vertigo, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, and sensory or motor impairment, sometimes with clumsiness in skilled acts.

PREVENTION

The probability of asymptomatic individuals developing atherosclerotic cerebral infarction has been examined by the Framingham study. Hypertension, diabetes, heart enlargement, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking elevate stroke risk, with cumulative risk escalating with age and concurrent risk factors. Effective blood pressure control emerges as a pivotal preventative measure against cerebral ischemia. Preventing recurrent attacks and infarction involves treating transient ischemic attacks and addressing cerebral atherosclerosis and emboli. Anticoagulation and surgical correction of arterial obstruction have been extensively evaluated. Additionally, Ayurvedic treatments offer promising alternatives, leveraging pulse diagnosis and lifestyle analysis for holistic management and counseling, yielding favorable outcomes.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at 9650696341

Leave a Reply