A gripping exploration of art, capitalism, and creative ownership, The Storyteller masterfully brings Satyajit Ray’s vision to life.

By Kalpana Pandey

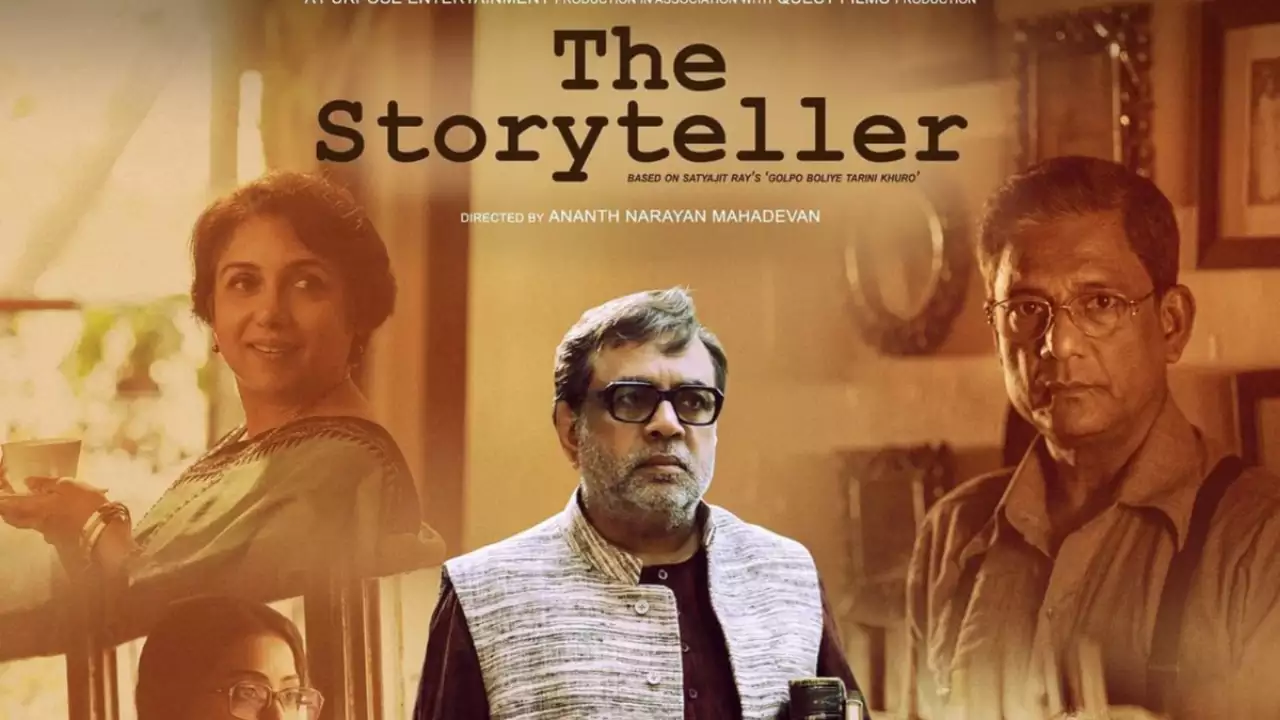

Based on Satyajit Ray’s short story “Golpo Boliye Tarini Khuro,” Ananth Mahadevan’s 2025 film The Storyteller delves into the timeless conflict between authentic labor and monetary gain. The narrative unfolds through the perspectives of two vastly different individuals: Tarini Bandyopadhyay (Paresh Rawal), an elderly Bengali storyteller with communist ideals, and Ratan Garodia (Adil Hussain), a wealthy Gujarati businessman suffering from chronic insomnia. Their juxtaposing worlds serve as a critique of a profit-driven system that frequently exploits creative endeavors. More than just an engaging story, the film raises fundamental questions about artistic ownership, recognition, and the resistance against intellectual exploitation.

At its core, The Storyteller highlights the real-world appropriation of artistic work. Tarini, deeply rooted in Bengal’s rich literary heritage, is hired by Ratan, a successful cloth merchant from Ahmedabad, who hopes that Tarini’s stories will help cure his sleeplessness. Initially, their arrangement appears straightforward—one man shares stories, while the other listens. However, the dynamics shift as Ratan’s true motives become evident. His past failures to win over his refined former lover, Saraswati (Revathi), despite his immense wealth, reveal a deeper insecurity. In an attempt to impress her, he begins to appropriate Tarini’s original narratives, presenting them as his own. This blatant theft mirrors how capitalist structures regularly strip creative individuals—writers, artists, and working-class intellectuals—of their labor, repackaging it for profit without acknowledgment.

Tarini’s reluctance to publish his stories stems from a deep-seated fear of failure, criticism, and commercial rejection. His creativity thrives in the ephemeral space of oral storytelling, unconcerned with financial success. Ratan, embodying the opportunistic nature of capitalism, exploits this vulnerability by seizing Tarini’s narratives and publishing them under his own name. This act of intellectual theft is not merely a plot device but a scathing indictment of a system that routinely commodifies art while erasing the identities of its true creators. Ratan, despite his deceit, exhibits no moral dilemma—his smirk as he reaps the benefits of Tarini’s work underscores the impunity with which the privileged appropriate the labor of the marginalized. This theme, central to Ray’s original story, remains a powerful commentary on the intersection of art and commerce.

Beyond the individual conflict, the film also explores the broader cultural struggle between dominant and regional identities. Kolkata, where Tarini resides, is portrayed as a city teeming with life, history, and tradition. The bustling fish markets, colonial-era buildings, and the communal spirit of storytelling reflect a culture where art is a shared heritage rather than a commercial commodity. In stark contrast, Ratan’s Ahmedabad mansion is depicted as a hollow monument to materialism, filled with expensive yet lifeless possessions—Picasso prints, unread books, and designer furniture—serving as mere status symbols. The film critiques this capitalist approach to culture, where art is reduced to an object of display rather than an expression of identity. This thematic tension—between the organic vibrancy of Kolkata and the sterile opulence of Ahmedabad—symbolizes the homogenization of diverse traditions in the face of market forces.

The film’s exploration of artistic integrity versus capitalist pressures culminates in a fascinating twist. As the narrative progresses, both Tarini and Ratan find themselves writing—one to reclaim his stolen work, the other as an act of imitation. This mutual transformation, though optimistic, underscores the film’s central message: creativity cannot be truly owned or controlled. A particularly poignant moment occurs when Ratan, a strict vegetarian, instructs his servant to feed the fish, inadvertently reducing Tarini to mere sustenance for his own gain. This subtle metaphor exposes the dehumanizing effects of exploitation.

Further reinforcing the film’s themes is the recurring image of a cat, a natural predator of fish, being forcefully fed a vegetarian diet. Eventually, the cat rebels, stealing fish from its owner’s tank—a metaphor for the tension between intrinsic desires and imposed constraints. The act of theft is presented not as wrongdoing but as a justified rebellion against unnatural suppression. In this allegory, the vegetarian food represents societal norms that stifle individual authenticity, while the stolen fish symbolizes the reclaiming of one’s true self. Ethically, the film challenges the audience to consider whether survival or conformity carries greater moral weight, drawing parallels to the broader struggle between artistic freedom and capitalist appropriation. Understanding this struggle, Tarini ultimately takes the cat with him to Kolkata, where he ensures it receives its rightful nourishment—an act that reaffirms his own artistic liberation.

The female characters in The Storyteller are depicted as strong, independent, and integral to the film’s message. Saraswati (Revathi), Ratan’s former lover, is a woman of principles who values integrity over wealth. Her decisive statement, “I might have managed with a businessman’s values, but not with a thief,” marks her as a figure of moral clarity, leaving Ratan behind without hesitation. Similarly, the librarian Suzi (Tanishtha Chatterjee) offers a confident, intellectual presence, adding depth to the film’s discourse on knowledge and artistic agency. Even Tarini’s late wife, who gifted him a pen as a symbol of encouragement, continues to inspire his creative journey. These women, rather than being passive figures, embody the progressive ideals championed by Satyajit Ray, enriching the film’s narrative with their resilience and wisdom.

Unlike the high-speed storytelling of contemporary cinema, The Storyteller adopts a meditative, deliberate pace, inviting viewers to savor life’s finer details. Ananth Mahadevan’s direction, coupled with Alphonse Roy’s evocative cinematography, captures nostalgic vignettes—hand-pulled rickshaws in Kolkata, intricate marble facades in Ahmedabad—creating a visually immersive experience. This unhurried storytelling style is a reminder that true art requires patience, sacrifice, and courage. In an era dominated by rapid consumption, the film advocates for the lost art of contemplation, reinforcing that the essence of storytelling lies not in its commercial viability but in its ability to inspire reflection.

The film’s impact is amplified by its powerful performances. Paresh Rawal embodies Tarini with a quiet strength, portraying a man who, despite betrayal, responds with measured wisdom rather than aggression. His decision to remain in Ratan’s home for months, refusing to be dismissed or devalued, is an act of subtle rebellion. In contrast, Adil Hussain masterfully conveys Ratan as a man trapped by his own insecurities—wealthy yet deeply unfulfilled. Their interplay forms the emotional core of the film, elevating its commentary on art, power, and justice.

Ultimately, The Storyteller is more than a retelling of Ray’s classic; it is a compelling exploration of creativity in a world governed by profit. The film urges us to reconsider how art is valued and who truly benefits from its creation. As Tarini finally takes ownership of his work, his wry remark—”Even copying requires brains”—serves as a sharp critique of a society that finds it easier to steal ideas than to nurture them. In the end, The Storyteller is a triumphant ode to artistic integrity, a call to reclaim creativity from market forces, and a reminder that true justice lies in recognizing the labor behind every story.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at Mob: 9082574315 [email protected]

Leave a Reply