From the trenches of India’s freedom struggle to the pages of literary history, Yashpal’s fearless voice echoes through time.

By Kalpana Pandey

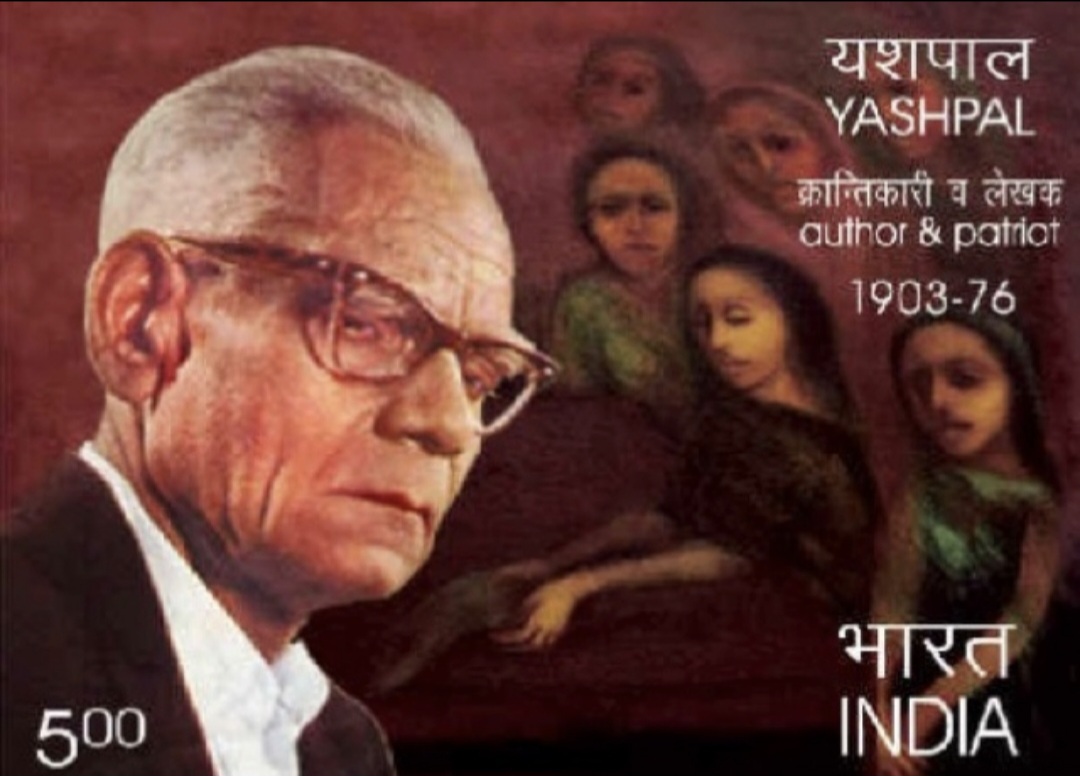

Renowned Hindi writer Yashpal, celebrated for his contributions to fiction, non-fiction, and revolutionary literature, was born on December 3, 1903, in Ferozepur, Punjab. His ancestry traces back to Bhumpal village in Hamirpur, Himachal Pradesh. His grandfather, Garduram, traded across various regions, while his father, Hiralal, worked as a shopkeeper and tehsil clerk, moving frequently for work. Despite their efforts, the family inherited little—only a small plot of land and a mud house. Yashpal’s mother, Premdevi, was a teacher at an orphanage in Ferozepur Cantonment and aspired for him to become a preacher of the Arya Samaj, sending him to Gurukul Kangri for his education.

Yashpal’s formative years were marked by the dual oppressions of British colonial rule and financial hardship. In his hometown, Indians could not carry umbrellas before the British, a glaring symbol of subjugation. Such humiliations ignited in him a deep resentment against the colonial rulers from an early age. The Non-Cooperation Movement led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1921 became his first foray into activism as a teenager. However, Yashpal soon grew disillusioned with the movement, finding its approach ineffective in addressing the struggles of India’s poor and marginalized. Determined to pursue more direct action, he enrolled at Lahore’s National College, founded by Lala Lajpat Rai. There, he forged connections with Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Bhagwati Charan Vohra, and became actively involved in Bhagat Singh’s Naujawan Bharat Sabha. Inspired by socialist ideals, Yashpal committed himself to the armed revolutionary struggle. The brutal lathi charge that led to Lala Lajpat Rai’s death during the anti-Simon Commission protests further galvanized his resolve, and he participated in the assassination of British officer J.P. Saunders.

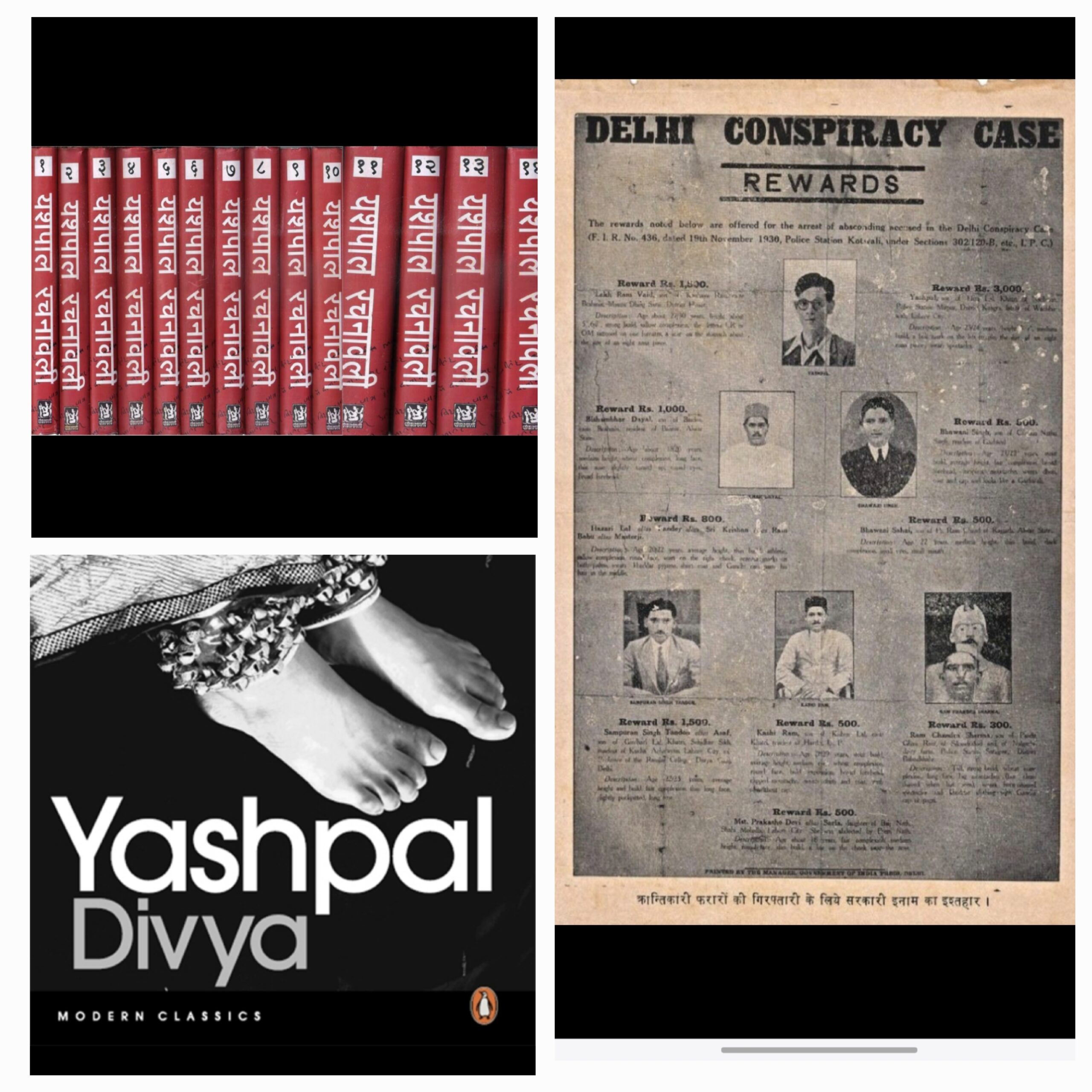

Yashpal’s revolutionary career reached a turning point in 1929 when he bombed a train carrying British Viceroy Lord Irwin, an act that heightened his notoriety. He was also involved in attempts to free Bhagat Singh and other revolutionaries, as well as in clashes with the police. During this period, he met Prakashwati, a 17-year-old revolutionary who shared his zeal for the freedom struggle. Trained in firearms by Chandrashekhar Azad, she became his trusted partner in both revolution and life. Following Azad’s death in 1931, Yashpal assumed command of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA). With a bounty of Rs. 3,000 on his head, he evaded capture for two years while continuing revolutionary activities, including manufacturing explosives. However, in 1932, he was apprehended by the British in Allahabad after a gunfight and sentenced to 14 years of rigorous imprisonment.

Prison became a transformative period for Yashpal. In a rare and historic incident, Prakashwati sought permission to marry him while he was incarcerated. Despite bureaucratic hurdles and objections, the marriage was solemnized in Bareilly Jail in August 1936. This event, widely covered by newspapers, prompted the British to later amend prison rules to prevent such unions. During his imprisonment, Yashpal immersed himself in literature, mastering French, Russian, and Italian, and began writing. His short story collections, Pinjre Ki Udan and Woh Duniya, were written during this time. His prison memoir, Meri Jail Diary, reflects his intellectual engagement with diverse ideologies, including Gandhi’s non-violence, Lenin’s socialism, and Freud’s psychoanalysis. These works revealed a restless mind evolving into a writer of exceptional insight.

Released in 1938 after refusing to renounce revolutionary violence, Yashpal faced dire financial circumstances. He and Prakashwati struggled to make ends meet, crafting and selling toys, collecting discarded materials, and making shoe polish. Eventually, they established a modest life in Lucknow. Using a hand-operated printing machine left from his revolutionary days, Yashpal launched the magazine Viplav (Revolution). Prakashwati, now a qualified dentist, supported the venture financially and later abandoned her practice to assist her husband. Viplav became a platform for diverse ideologies, featuring contributions from Gandhians, Marxists, and social revolutionaries. Its popularity led to the launch of an Urdu edition, Baaghi. However, British authorities frequently censored the magazine, imposing heavy fines and restrictions. By 1941, relentless persecution forced its closure. After independence, Viplav briefly resumed publication but was permanently shuttered due to new press regulations.

Despite setbacks, Yashpal continued to write prolifically. His novel Dada Comrade (1941) explored the psychological turmoil of a young revolutionary, drawing both acclaim and criticism. His later works, including Deshdrohi and Jhutha Sach, cemented his reputation as a literary giant. Yashpal’s writings were deeply rooted in realism, challenging Gandhian ideologies and advocating for socialism. His fearless spirit extended beyond his revolutionary activities. In one memorable incident, a British officer insulted him during a meeting about Viplav. In response, Yashpal mirrored the officer’s dismissive posture, leaving him stunned. This defiance exemplified his unyielding nature, whether in politics, journalism, or literature.

Yashpal’s transition from revolutionary to writer marked a unique trajectory in Indian history. Through his writings, he critiqued societal inequalities, colonial oppression, and the limitations of non-violent resistance. His works remain a testament to his vision of a just and equitable world, inspiring generations of readers and activists. Today, Yashpal is remembered not only for his contributions to India’s freedom struggle but also for his indomitable literary voice, which captured the complexities of a nation in transition.

Yashpal, a celebrated revolutionary and literary icon, blended Marxist ideology with the struggles and aspirations of Indian society in his writings. Among his early contributions was a simplified book titled Marxism, based on Karl Marx’s theories. Written to make socialism accessible to both its supporters and skeptics, it remains a widely read introduction to Marxism. Yashpal’s bold and sharp writing style resonated with readers and critics alike.

On June 8, 1941, Yashpal was arrested under the Defence of India Act, though his friends secured his release on bail. Anticipating further imprisonment, he published Gandhivad Ki Shav Pariksha in August 1941. The book, a critique of Gandhian ideology, exposed the limitations of the Gandhian movement as perceived by a young revolutionary. Its impact was significant, with Dr. Bhadanta Anand Kausalyayan, a Buddhist monk and scholar, hailing it as one of the most important books of the year.

In 1942, Yashpal published Chakkar Club, a satirical critique of pretentious intellectuals, and Tarka Ka Toofan, a collection of 16 stories delving into human conscience and logical thought. His novels, including Dada Comrade (1941), Deshdrohi (1943), Divya (1945), and Jhutha Sach (1958), explored themes of class struggle, social inequality, and human desires.

His 1945 novel Divya introduced a rebellious narrative to Hindi literature. The story follows Divya, a woman from a noble family who grapples with caste politics and religious conflicts. Betrayed by her lover, she rejects societal constraints and pursues independence, ultimately realizing that only a prostitute can claim true freedom. Set against the ideological clash between Hinduism and Buddhism in the first century BCE, the novel is a rich tapestry of historical imagination and social commentary.

Yashpal’s 1946 novel Party Comrade, later renamed Geeta, centered on a communist activist, Geeta, who dedicates her life to the party’s cause, navigating the challenges of a male-dominated society. The book captured the spirit of political commitment during the tumultuous years of the sailors’ rebellion. That year also saw the publication of Phulo Ka Kurta, a collection of stories marked by narrative depth, psychoanalysis, and satire.

His stories, including those in collections like Abhisapta and Gynandaan, often focused on marginalized communities, class struggles, and human ambitions. Yashpal did not shy away from controversial subjects. His 1962 novel Barah Ghantey challenged societal norms, exploring themes of love, morality, and personal freedom. Through the story of a widow and a widower navigating societal judgment, Yashpal questioned traditional values and emphasized the importance of individual agency.

Yashpal’s magnum opus, Jhutha Sach (The False Truth), is a two-part novel widely regarded as a masterpiece of Hindi literature. Set against the backdrop of Partition, it portrays the lives of two families as they navigate the chaos and bloodshed of pre- and post-Partition India. Critics likened it to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and The New Yorker called it “perhaps the greatest novel about India.” The book’s balanced portrayal of Hindu and Muslim perspectives, along with its critique of Congress leaders in post-independence India, cemented Yashpal’s reputation as a fearless writer.

Despite his literary acclaim, Yashpal faced frequent opposition. In the early 1950s, amidst government crackdowns on communists, he was imprisoned once more. When his wife questioned his arrest, Chief Minister Govind Vallabh Pant reportedly replied, “His writing makes people communists and recruits them to the party.” Yashpal remained unperturbed, continuing to write with his characteristic boldness.

His political and social commentary extended to works like Ram Rajya Ki Katha, critiquing growing inequality in post-independence India. In his later years, he authored novels like Teri Meri Uski Baat (1974), addressing the 1942 Quit India movement and redefining the concept of revolution as societal transformation rather than mere political change.

Yashpal’s personal life was marked by resilience and humor. Despite opposition from religious fanatics, he remained steadfast in his progressive views. He often joked about his ambiguous caste and religion, reflecting his rejection of rigid social identities. On one occasion, when questioned about starting a publishing business, he defended his decision, emphasizing the importance of ideological and economic independence.

Yashpal’s writings were a powerful tool for social reform. His stories and novels frequently featured strong women characters who challenged societal norms. He critiqued the rigid customs of all religions, often at great personal risk, and advocated for the rights of Dalits, marginalized groups, and women. His progressive outlook resonated with readers and earned him both accolades and controversy.

In recognition of his contributions, Yashpal was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1970, along with other honors such as the Soviet Land Nehru Award (1970) and the Mangala Prasad Award (1971). His influence extended beyond literature; his work remains a vital document of India’s freedom movement and the socio-political landscape of post-independence India.

Yashpal passed away on December 26, 1976, while working on the fourth volume of his memoirs, Sinhavalkan. His death marked the loss of a revolutionary thinker and writer who championed social and political change through his works. From his critiques of Gandhian ideology to his unflinching portrayal of Partition, Yashpal’s legacy continues to inspire readers and writers alike.

Today, his revolutionary and literary contributions remain as relevant as ever, serving as a testament to his vision of a just and equitable society. His writings remind us that the pen can be as powerful as the sword in the fight for freedom and social justice.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at [email protected]/9082574315

Leave a Reply