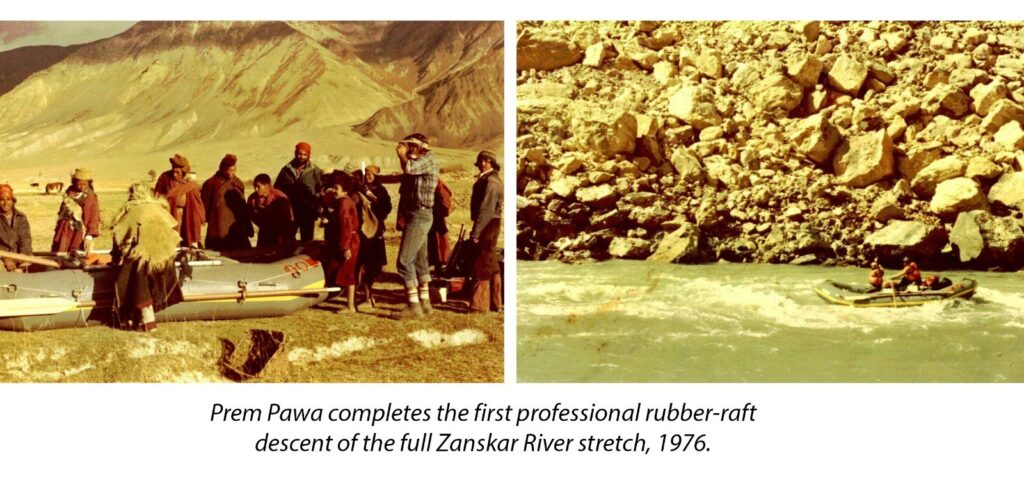

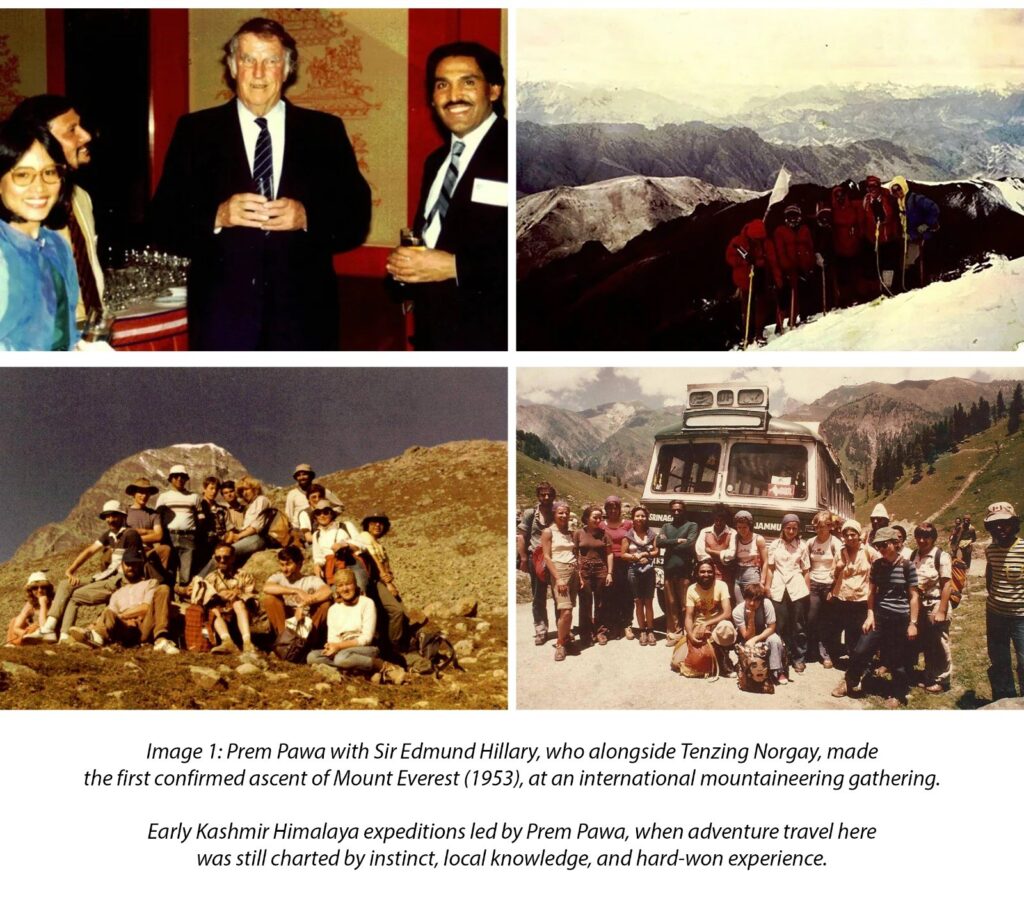

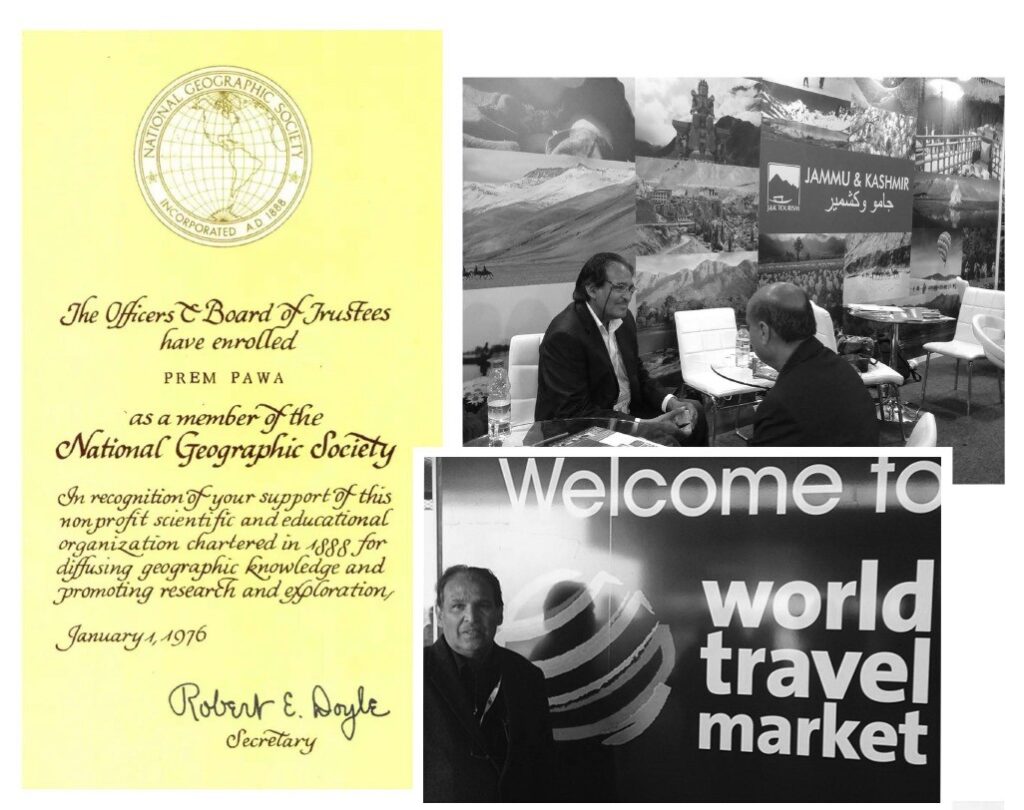

Prem Pawa hails from Srinagar and is an adventure tourism pioneer who began his career in the early 1970s. Trained at the Indian Mountaineering & Skiing School in Gulmarg, he is a permanent member of the National Geographic Society. He is credited with landmark “firsts,” including rafting the full stretch of the Zanskar River in Ladakh and leading some of the first Western adventurers into Ladakh in 1974.

By Prem PAWA

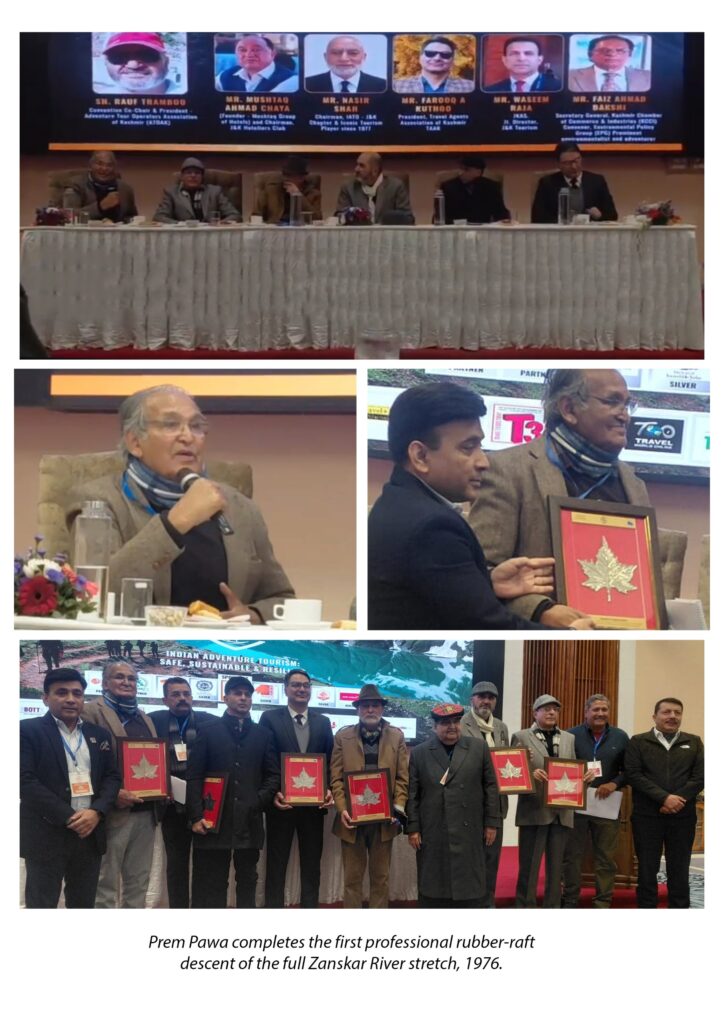

This week, I found myself addressing fellow adventure tour operators at a convention in Srinagar, in a hall overlooking the shimmering expanse of Dal Lake. It was the 17th Annual Convention of the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India (ATOAI), held at the Sher-i-Kashmir International Convention Centre (SKICC), a gathering supported by the Government of Jammu & Kashmir to showcase the UT’s resurgence as a top adventure destination.

Through the glass windows, I could see the same lake where I once guided visitors in flower-decked shikaras (traditional wooden boats) decades ago. The venue bustled with energy, national and local operators mingled with policymakers under the convention’s theme, “Indian Adventure Tourism: Safe, Sustainable & Resilient”. In the inaugural session, dignitaries like Omar Abdullah, the Chief Minister of J&K, lent their weight, highlighted how far we’ve come. The Chief Minister not only inaugurated the event but actively pitched Kashmir as one of the world’s premier adventure hubs, stressing our mountains and rivers give us a natural edge for skiing, mountaineering and trekking if developed responsibly. At one point, a colleague, Rauf Ahmad Tramboo, Convention Co-Chair & President, ATOAK (Adventure Tour Operators Association of Kashmir (ATOAK), turned to me with a thoughtful smile. “What has changed in all these years of adventure tourism?” he asked. His simple question made me pause as the lively conference scene faded into the background. In that moment, my mind wandered back over a half-century of experiences.

In early 1970s, when I was a young mountain guide and adventure tours manager and Kashmirs high meadows were known only to shepherds and a few intrepid explorers. In those days, places like Gulmarg, Sonamarg, and our alpine lakes were quiet paradises visited by global Himalayan explorers. I remember leading one of the the very first, or possibly the first group of foreign trekkers into Ladakh when it was first opened in 1974 and certainly the first to raft the mighty Zanskar in Ladakh. All of this earning myself a permanent membership of the National Geographic Society.

We had no phones, no modern equipment, just stout boots, paper maps, and the guidance of experienced memory and local shepherds who knew the routes by heart. Back then, adventure tourism in Kashmir was a evolving idea. Visitors came for the houseboats and gardens; some ventured into the high passes. We blazed new trails together with our guests, often literally cutting paths through virgin forest. I’ll never forget a dawn at Naranag: standing with a American trekker on a ridge, watching the sun paint the snow on Mount Harmukh golden. He whispered, “It really is heaven.” And indeed, to us, it was. The thrill of those first expeditions, sharing Jammu Kashmir’s pristine lakes, glaciers and peaks with curious travellers, left an imprint on my soul. In those days, the only people we encountered in the mountains were Gujjar shepherds tending their flocks. Tourism was modest and largely seasonal. Yet, word spread slowly. By the 1980s, Kashmir was earning its place on the global trekking map, and our valley saw more and more adventure lovers arriving each summer.

Then came the storms, dark years that Kashmir would never forget. Starting around 1989, as a result of the terrorism and insurgency in the Valley almost overnight our bustling tourist season evaporated. Until the late 1980s, we had seen record tourism around 700000 tourists visited in 1987 alone, but just three years later, as violence gripped Kashmir, the number fell to a under 6000. The high meadows fell silent; trekking huts and equipment gathered dust. Those of us who survived on tourism burned through our savings and took whatever odd jobs we could find to sustain our families. Foreign governments issued stern travel advisories, Britain for example warned its citizens away from Kashmir for decades, only partially lifting its advisory in 2012, they still have limitations on anything beyond Jammu, especially after the Baisaran terrorist attacks earlier in May this year. For the better part of the 1990s, I didn’t curate a single trek in Kashmir; not because I lost my passion, but because there were no tourists due to the situation in the valley. I recall checking my old trekking logbook of early 1990s and seeing blank pages where once each summer week had a new group assigned. We watched as the “golden age” of the 1970s and 80s faded into memory, uncertain if it would ever return.

Yet even in those dark times, the mountains remained as majestic as ever, silent witnesses to our turmoil. Occasionally, a truly adventurous soul would appear, a journalist, a documentary filmmaker, or just a stubborn backpacker, and I’d gladly take them into the hills, assuring them with a forced smile that we would be safe. Each such rare trek felt like an act of resistance, a reminder that the spirit of adventure in Kashmir was bruised but not broken. We learned resilience the hard way, telling ourselves that if and when peace came, we would be ready to reopen the trails and welcome the world back.

By the late 2000s, the tides began to turn. Sporadic violence still occurred, but tourists gradually trickled back, and then poured in. As the situation improved, domestic travellers from across India also started discovering Jammu Kashmir’s adventure opportunities, not just its shikara rides. The momentum built, and by 2011-2012 we hit new heights, literally and figuratively. 2012 saw the highest tourist arrivals in our history, over 1.3 million visitors in that year alone. In early 2013, I curated my first sizeable group of Skiers of over 100 skiers from the adventure club of Indore that winter in years, it felt like stretching muscles that had long been idle.

There were setbacks even during this period of revival. The years 2008, 2009, and 2010 brought renewed challenges, as the Yatra, a sacred Hindu pilgrimage trek tracing the footsteps of saints and sages of Kashmir as chronicled in the Rajatarangini, was repeatedly disrupted. We weathered natural disasters like the devastating floods of 2014, and political tremors that led to shutdowns in 2016 and again in 2019. Each time, tourism faltered.

I recall August 2016 vividly, gathering my team as another official advisory urged tourists to leave, a moment that felt hauntingly like the 1990s. And yet, each time, Kashmir proved its resilience. Within months, sometimes even weeks, the tourists returned, drawn by the magnetic pull of our landscapes and the quiet courage of its people. But there are moments that weigh heavier than others. The barbaric attacks of April 2025 in Baisaran remain a dark and painful stain, an incident that forces us to bow our heads in collective grief and reflection, all the more so as we strive to welcome trekkers and mountaineers to our pristine mountains and sacred high meadows.

Which brings me back to this week’s convention in Srinagar. I walked into SKICC with the winter light on Dal Lake and a strange familiarity in my chest, as if time had folded neatly on itself. Outside, the shikaras still moved with their old grace; inside, the room carried a new kind of energy. An adventure gathering of such scale in Srinagar, after everything we have endured, felt like a quiet victory that did not need applause.

When I was kindly invited to the panel, I looked across the hall and saw the full arc of our story: officials who once spoke only of containment now speaking of possibility; veterans whose eyes remember empty seasons; young entrepreneurs who have never known the long silences of the 1990s but carry fresh confidence in their stride. The Chief Minister’s message was measured and, to my mind, correct: yes, promote adventure tourism, but build it safely, build it sustainably, and build it with open eyes to climate change. His last point landed like a stone in still water.

Without straying into questions of peace, security, facilities or infrastructure, I want to stay with the actionable, what operators, guides, and guests can do on the ground. I have watched slopes that once held snow until spring turn bare too soon; I have seen streams run lower, glaciers retreat, and wildflowers fade in patches where they once returned faithfully. Nature does not forgive repeated neglect. The mountains are not recyclable. The meadows are not a stage. They are an ecosystem, and every trek is a test of how we preserve them for future generations.

And I will continue of what I did not have time to say. Kashmir’s next leap cannot be only bigger numbers or louder campaigns; it must be better practice, quiet, consistent, and uncompromising. Because in the mountains, reputation is built the way a trail is built: one careful step at a time, and lost in a single careless moment. Standards are not paperwork; they are survival. A guide who can read weather, manage altitude, and keep a team calm matters more than any brochure. First-aid must be reflex, not a certificate. Rescue protocols must be rehearsed before they are needed. Camps must vanish in the morning as if they were never there. Waste must return with us. Water sources must be protected. Wildlife must be watched with reverence, not chased for photographs. This is not luxury, it is the minimum price of operating in a living ecosystem.

I have seen how places like Europe and Japan protect their mountains through discipline: structured training, regular workshops, audits, and a shared code that every operator respects because everyone understands what is at stake. Jammu and Kashmir deserves the same seriousness, not because we want to imitate others, but because our terrain demands it, and because our innocence has already been tested by history. If we want trekkers and mountaineers to return year after year, and if we want our children to inherit high meadows that are still clean, still wild, still sacred, then we must build a culture where safety and sustainability are not slogans. They are habits. They are pride. They are the way we prove that this revival is not temporary acknowledgment, but a long, steady guardianship of the land.

I did speak to some of these essentials, and as I wrapped up my reflections at the conference, a gentle applause rose. Less for me, perhaps, and more for the idea that Jammu and Kashmir can do this right. Many in the audience had lived through pieces of this journey themselves; others, younger, told me later that my stories gave them a new perspective.

That evening, I stood by the Dal Lake shore, the city lights danced on the water, and I could faintly see the silhouettes of the houseboats and the outline of mountains beyond. I thought about how far Jammu and Kashmir’s adventure tourism has come, from an era of innocence to upheaval, and now to revival and doing it right. Everything has changed, yet in the most important ways, nothing has changed. The mountains still stand, indifferent to human troubles, waiting to bestow wonder on whoever ventures up their slopes. And I, now a grey-haired advocate of nature, still feel the same flutter in my heart before every trip into those hills.

So, what has changed? I would say: almost everything, and almost nothing. We have more tourists, more support, and more knowledge now, a world apart from the 1970s, which makes Jammu and Kashmir’s adventure scene stronger than ever.

But the essence of why we do this, the joy of discovery, the bond with nature, and the hope that adventure brings, remains as true as it ever was. Standing here in Srinagar, I felt the same awe I did as a young trekker and mountaineer. After half a century, Jammu and Kashmir still has the power to humble and inspire us, yet for that magic to survive the pressures of scale, it must be protected by better practice and discipline, that is the enduring magic that no passage of time can dim.

Prem PAWA is a adventure tourism icon from Srinagar, who started his career in tourism during the early 1970s as a mountaineer and trekker in Kashmir and has continued to lead and operate tourism across J&K and beyond.

Leave a Reply