Dr. Rafeeq Masoodi’s latest collection of prose poems, Bey Pie Talash, is a lyrical journey through faith, memory, and the heart of Kashmir.

By Rayees Ahmad Kumar

Dr. Rafeeq Masoodi is a name that resonates deeply within Kashmir’s cultural and literary circles — a broadcaster, administrator, poet, and philanthropist whose work has shaped generations of listeners and readers alike. Having helmed premier institutions such as Vividh Bharati, Radio Kashmir, Doordarshan, and the J&K Cultural Academy, and later serving as Additional Director General of Doordarshan and the Directorate General of Development Communication Division in New Delhi, Dr. Masoodi’s journey has been one of communication in its purest form — from airwaves to verses. A translator of repute, he has brought celebrated works like Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas and Vishnu Prabhakar’s Ardh Narishwar into Kashmiri, bridging linguistic and cultural worlds with care. His earlier poetry collection Panun Dod Panin Dag (My Pain, My Affliction) found resonance beyond language barriers, translated into multiple tongues and celebrated for its lyrical introspection.

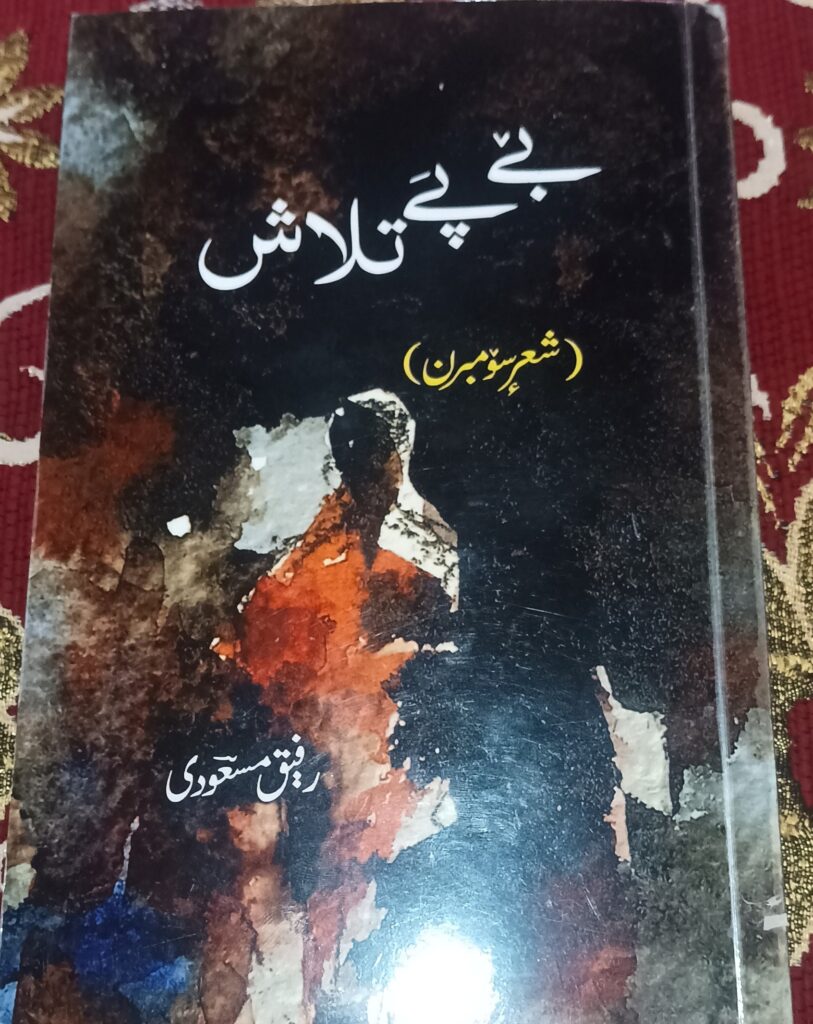

Now, with his latest offering Bey Pie Talash (In Search of Myself), Masoodi deepens his poetic journey. The book, released recently at Srinagar’s Tagore Hall in a grand literary gathering hosted by Adbi Markaz Kamraz—of which he is patron—cements his stature as one of Kashmir’s most versatile literary voices. Published by Taj Printing Service, Delhi, Bey Pie Talash comprises 138 prose poems across 218 pages, adorned with a tasteful cover designed by Javaid Iqbal and Jameel Ansari. The dedication page reads like a love letter to family and lineage — “To my beloved mother, Muntazir, Umaia, Ashwaq, Nihad, Niyusha, and Amal Aashia” — a gesture that sets the emotional tone of the work.

In his proem Kaethi Manz Bawaan Kath, noted academician and poet Prof. Shad Ramzan traces the evolution of Kashmiri poetry — from the mystic verses of Lal Ded and Sheikh-ul-Alam to the modernist cadences of Nadim, Mehjoor, Rahi, Firaq, Kamil, and Aazim — placing Masoodi’s work within that enduring continuum. Prof. Nazir Azad, in his foreword, highlights the collection’s literary depth and the author’s ability to interlace faith, memory, and social consciousness in a language both intimate and universal.

Masoodi opens his collection with a hymn to the Almighty, a poetic invocation where the divine manifests in “the blue skies, the green of earth, and the light of the sun.” His verses shimmer with gratitude and humility, seeking refuge in the sacred. Another poem extols the Qur’an, describing the sanctity of recitation before dawn — tears falling like drops of purification. In a moving ode to the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), Masoodi meditates on mercy and moral awakening. He reminds readers that without the Prophet’s guidance, humanity might never have understood unity, compassion, or the essence of monotheism. A devout follower of the Ahl al-Bayt, Masoodi’s poems on the tragedy of Karbala and the martyrdom of Hazrat Hussain (RA) evoke timeless sorrow and reverence. His faith finds expression not only in devotion but in the persistence of moral memory — how martyrdom continues to inspire centuries later. In another poem, he seeks the blessings of Kashmir’s patron saint, Sheikh Hamza Makhdoom (RA), imploring for guidance and light.

In Kahin Chuna Alaw Bozan, Masoodi paints silence as a haunting character — so deep that “a mother forgets her child, the infant no longer cries, and even the wind hides in a cave.” This eerie imagery captures the essence of grief unspoken — the kind of silence that Kashmir knows too well. In Zindagi Akh Tueka Tapuk, inspired by a tragic accident at Trehgam Chowk on June 29, 2016, he writes of the fragility of life: how in seconds, splendor turns to rubble and kings to beggars. These poems, though rooted in personal memory, echo collective pain — the suddenness of loss that redefines existence. In Yei Zihea Zahn, he returns to childhood, flipping through black-and-white photographs, longing for the simplicity of “those monochrome days.” Nostalgia here becomes a metaphor for innocence lost amid modern chaos.

One of Masoodi’s most striking poems, Taraqi (Progress), critiques the ironies of modernity. He observes how today’s children speak English fluently and master digital games but can hardly utter a sentence in Kashmiri — a language “rich in the world’s finest literature” now receding from homes. “It can’t be called progress,” he writes. “It is devastation.” At the shrine in Saed Saib Ni Daedi Tal, the poet finds unity in faith — “no one looks like a foe; every face glows as if washed by Zamzam.” Whether referring to Syed Sahib of Sonwar or another saint, Masoodi’s lines honor the mystical oneness that Kashmir’s shrines have long symbolized. In Atha Chi Talismi Asan, he marvels at the “magic in every hand” — some turn pebbles into rubies, others craft beauty from charcoal. The poem is a tribute to human creativity, talent, and divine blessing.

Masoodi’s reflections on human nature carry philosophical weight. In Hasad (Envy), he defines jealousy as “born from a black heart,” a shadow that corrodes relationships and happiness. Dardrai explores pain as a paradox — how humans cry for themselves yet brave the storms unflinchingly. In Khata (Error), he reminds readers that “to err is human,” but repentance redeems. Through such poems, Masoodi’s moral voice shines: introspective yet never moralizing, his tone remains empathetic, grounded in human vulnerability.

Among the most poignant pieces is Abaji, a tribute to his late father. Nearly five decades after his passing, the poet measures the enduring presence of loss, recalling piety and love with unpretentious grace. “He still walks beside me,” the poem seems to whisper — an echo of memory that time cannot erase. In Mouj Kashiri Rath Wandai, he mourns the decline of Kashmir itself — once “thriving through all means,” now wounded by history and circumstance. Using layered metaphors, he transforms personal pain into collective lament. The title poem, Bey Pie Talash (In Search of Myself), is perhaps the emotional center of the book. Here, the poet wanders through “lanes, streets, blazing fires, and blooming roses,” asking — what is it that I truly seek? This existential question lingers, unanswered yet luminous, inviting readers to turn inward and examine their own quests.

Masoodi’s concluding poems, like Myoun Sarmayi (My Wealth), tie his personal story together — his “pains, afflictions, and encounters” as his real treasure. For him, poetry is both inheritance and offering, a way of preserving the soul’s testimony. Three of Kashmir’s literary stalwarts — Farooq Nazki, Shehnaz Rashid, and Ayoub Sabir — have lauded Dr. Masoodi’s craftsmanship, calling him “a skillful litterateur who knows how to sculpt feeling into verse.” His poems stand out for their quiet dignity, emotional intelligence, and precise imagery. Masoodi’s language flows effortlessly between sacred and secular, between the deeply personal and the culturally universal. His poetry is not merely written — it is lived. Each line carries a pulse of experience, the rhythm of a heart that has witnessed beauty and brokenness alike.

Bey Pie Talash is not just a collection of prose poems — it is a mirror to the Kashmiri psyche, reflecting its faith, nostalgia, and sorrow. Dr. Rafeeq Masoodi’s voice joins the timeless chorus of poets who turned pain into prayer and memory into art. For lovers of literature, faith, and language, this book is not merely to be read — it is to be felt. In its pages, one does not just find the poet; one finds oneself.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine.

Leave a Reply