The Kasaba, a symbol of grace and dignity, is disappearing from Kashmir’s streets. But in a moment of reflection, one woman’s legacy reminds us of a shared heritage that transcends generations and divides.

By Khursheed Dar

It was one of those quiet autumn afternoons when the chinar leaves had just begun their graceful descent—rust-red and golden, spinning slowly in the breeze like burnt memories adrift. The sky wore a muted hue, and the air carried that familiar fragrance of smoke and season’s end. I had gone to the shrine of Hazrat Syed Janbaz Wali (RA), a sanctuary nestled in silence, to offer my prayers and pay homage—to find a few stolen moments of stillness in a world that rarely pauses. But what I encountered instead was not stillness. It was a story—one not etched in ink, but wrapped in wool, woven with silence, and stitched into the fabric of time.

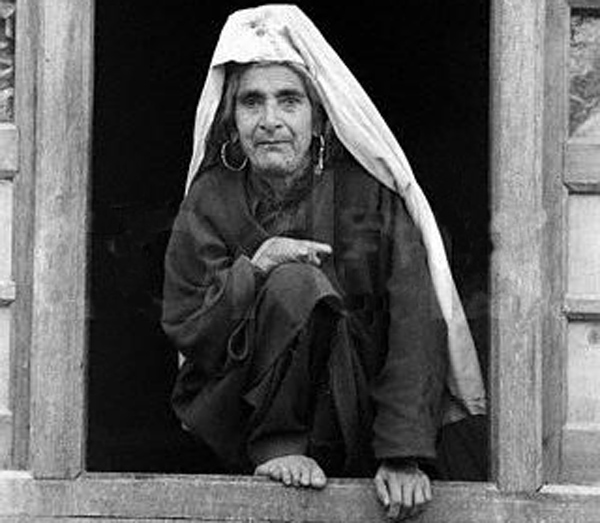

She sat under the grand chinar tree that stood like a sentinel at the shrine’s edge—majestic and weathered, its sprawling branches shielding not just the earth beneath but centuries of memories and unspoken prayers. An old woman, stooped with age but unbowed in spirit. Her posture was still, her silence dignified. She looked like she had stepped out of a fading photograph—a living echo from a time Kashmir now only remembers in fragments. Her presence was less of an interruption and more of an inheritance.

Her face was deeply lined, each crease a story in itself—of loss and love, of harsh winters and warm hearths, of fields tilled and children raised. Her eyes, though clouded by age, still held a spark of kindness, and her lips curled ever so slightly into a smile, as if she were revisiting a memory too sacred to be spoken aloud.

Nearby, a family bustled about in soft celebration—a traditional “Nazar” ceremony was underway. A baby’s first haircut, performed with gentle hands and reverent prayers. The air was tinged with the aromatic notes of “Kahwa,” steeping in a brass samawar that hissed quietly, as if murmuring its own blessings. Sugar cubes passed from hand to hand. Laughter drifted into the air like threads of incense smoke. The moment was tender, sacred, ordinary. But I kept looking at her—the old woman who sat apart, yet somehow belonged more than anyone else in that frame.

She wore a Kasaba—a traditional headpiece of Kashmiri women, but not the kind you see today in stylized wedding portraits or folkloric museum displays. This was the original—a heavy, hand-stitched crown of white cotton, wrapped around her head with both precision and pride. It bore the weight of generations and the scent of her grandmother’s lap. It wasn’t a fashion statement. It was remembrance rendered in cloth. A living heirloom. A story stitched in silence.

“My grandmother gifted it to me,” she said softly, catching my gaze. Her voice was gentle, feathered with time. “I wore it the day I got married. So did my mother. And her mother before her.”

She said no more—and she didn’t have to. The Kasaba spoke in her stead. It told of Kashmiri women who walked long distances with firewood on their backs and dignity on their brows. It whispered of festivals and family gatherings, of weddings lit by oil lamps and of whispered prayers folded into dawn. It reminded me, too, that the Kasaba wasn’t exclusive to Muslim women. Once, it crowned the heads of both Muslims and Kashmiri Pandits—a shared tradition in a shared land, worn with equal reverence. A now-forgotten sisterhood, once united by thread.

The baby let out a sharp cry as the scissors snipped his first lock of hair. The mother leaned in, soothing him with kisses and whispered reassurances. Kahwa was poured into tiny porcelain cups, and conversation fluttered around like autumn leaves. But my attention remained tethered to her—the old woman beneath the chinar, sitting with a kind of stillness that only time can teach.

Later that evening, as dusk fell like a slow curtain over the valley, I couldn’t shake her presence from my thoughts. The Kasaba she wore stayed with me—an emblem of a tradition slowly fading into shadows. Today, such pieces live mostly behind glass at places like Meeras Mahal in Sopore, or lie tucked away in grandmother’s trunks, untouched and unremembered. The newer generations may wear lighter versions, often for photo shoots in Mughal gardens—pretty props in curated nostalgia. The meaning is dissolving. The soul is being filtered out, replaced by selfies.

But on her—on that particular day—the Kasaba was alive. It breathed. It remembered. It bore the silent elegance of everything we are in danger of forgetting.

When she finally stood to leave, I noticed how slowly she moved, as though time itself was reluctant to let her go. The light softened around her, halo-like. I felt something tighten in my chest—a strange ache, the kind you feel when something precious slips through your fingers just as you begin to understand its worth.

That night, sleep eluded me. I kept thinking of her—the old woman with the Kasaba, and the last smile of a tradition silently walking out of our lives.

To borrow the poignant words of Dr. Rafeeq Masoodi—scholar, writer, and a passionate custodian of Kashmiri heritage—“Kasaba was a symbol of grace, a metaphor of creativity, and an honor in our childhood.” Seeing a woman wear it once evoked instant respect. Sadly, like so many of our cherished customs, it is receding into the folds of history. Yet, through efforts like Meeras Mahal in Sopore, Dr. Masoodi continues the uphill battle to preserve, document, and revive this cultural gem—so that the Kasaba may not just survive, but find meaning in the hearts of a new generation.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at [email protected]

Leave a Reply