Once bound by trust, generosity, and neighbourly care, Srinagar’s historic Downtown now struggles with silence and detachment.

By Syed Majid Gilani

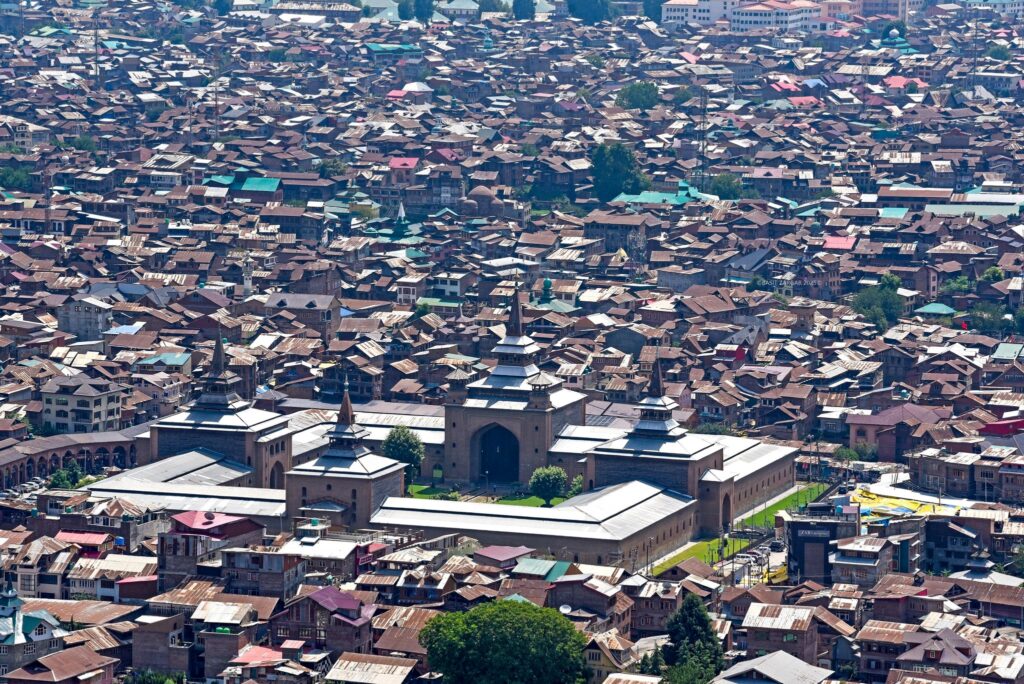

There was a time, not so long ago, when life in Srinagar’s Shehr-e-Khaas—the historic Downtown—moved with a rhythm both gentle and dignified, woven together by a spirit of simplicity and contentment. The narrow lanes, with their carved wooden houses leaning against each other like guardians of memory, the bustling courtyards where laughter mingled with the call of street vendors, and the centuries-old mosques that punctuated the skyline, were not just structures of brick, mud, and timber. They were living witnesses to a society where neighbours were kin and every household a part of one greater whole. Modest homes and limited means never diminished the richness of human bonds, for generosity was measured in deeds, not possessions, and relationships were shaped by unspoken understandings that only true communities nurture.

In those days, responsibility for society was not outsourced to institutions or law; it was carried on the shoulders of the people themselves. Neighbours looked out for one another not as an intrusion but as a moral duty. It was normal for an elder to stop a young boy on the street to ask where he was headed, or to gently admonish a girl for wandering out late. Such questions carried no sting of suspicion or offence; they were born of genuine care and a desire to guide the young along the right path. The rebuke of an elder was not feared but respected, for it came not with arrogance but with affection.

Perhaps the most beautiful aspect of Shehr-e-Khaas was the way its people shared not just space, but also their lives. A special dish in one household—whether Tehri, Halwa, Gaadi, Paachi, Houk Suen, or the winter delicacy Harisa—inevitably found its way to the neighbour’s kitchen. These gestures of sharing were not ritual or formality; they were silent declarations of belonging. Festivals, weddings, and even small bursts of joy spilled across walls and courtyards, binding the neighbourhood in collective celebration. Happiness was never hidden behind doors, and sorrow was never endured in solitude.

The soul of this society extended beyond homes into its communal spaces. The waani pend, Kander Waan, hamams, and Naid Waan were the informal parliaments of Downtown. These gathering spots, alive with debate and chatter, brought together men of every class and age. News, politics, disputes, and moral questions were discussed openly, with respected elders guiding the conversations. Decisions were not imposed by authority but reached through consensus, carrying weight because they were infused with honesty and concern for the community’s good. Today, those vibrant forums are silent, their role in nurturing unity and wisdom almost forgotten.

Equally vital were the social checks and balances maintained by elders, relatives, and family heads. These guardians of morality did not hover with suspicion but watched with wisdom, always ready to intervene with fairness. Conflicts within families were seldom left to fester. Respected figures would gather the parties, listen patiently, and offer judgments aimed at peace rather than punishment. Their authority was moral, not legal, but it carried more weight than court decrees because it sprang from sincerity and collective trust.

Women, too, were protected within this framework of concern. If any mistreatment occurred in a home, it seldom went unnoticed. The women of the neighbourhood, sharp in sensing unrest, would step in quietly—counselling, comforting, or even collectively intervening. If a married daughter lingered too long in her parental home, gentle inquiries followed—not to intrude, but to ensure her marriage was intact. Such checks, subtle yet powerful, kept relationships from unravelling in silence.

Children were raised not by parents alone, but by the whole neighbourhood. Respect for elders was instilled not through lessons but through lived experience. A child caught misbehaving in the street could expect correction from any elder, and the parents would welcome it. No father or mother felt slighted by another’s intervention; they saw it as collective parenting, a way of shaping responsible citizens. To disrespect an elder was considered not just mischief but a moral failing, a stain on the family’s honour.

The poor and needy were never abandoned. If illness struck or work dried up, the neighbourhood quietly rallied. Meals appeared at the doorstep, small financial help was offered discreetly, and dignity was preserved. Poverty never meant humiliation, for the unwritten law of Shehr-e-Khaas was that no one would be left hungry, no one left alone in despair.

Relationships thrived on presence, not distance. In those days, the absence of telephones and instant messages was not a handicap but a blessing. People knocked on doors to share happiness, to mourn a death, or simply to sit in companionship. Kehwa and Noon Chai flowed endlessly as hearts poured themselves out in conversation. Presence spoke louder than words; a hand held or a silent embrace carried meanings no phone call could replicate. Crime was rare, moral decay minimal, because the fabric of society was so tightly woven with empathy, responsibility, and guidance.

When tragedy struck—be it a death, an accident, or financial hardship—the entire mohalla came together. Neighbours cooked meals for the bereaved, sat in their homes to offer strength, and did whatever was required without waiting to be asked. Solidarity was instinctive, not planned. Comfort was given not through speeches but through presence, through the assurance that no sorrow would ever be borne alone.

This was the Srinagar of old, with Shehr-e-Khaas at its heart, where lives may have been materially modest but were spiritually abundant. Yet today, those bonds are fraying. The same streets that once rang with laughter and greetings now echo with silence and hurried footsteps. People retreat behind closed doors, joys are confined to nuclear families, and sorrows too often pass unnoticed. Disputes that once found resolution under the shade of wisdom now pile up in courtrooms, cold and distant. The absence of social checks, the fading watchfulness of elders, and the neglect of collective responsibility have left a void, one that laws and institutions struggle to fill.

Respect for elders, once the lifeblood of the community, has diminished, leaving younger generations adrift. The culture of collective parenting has faded, replaced by a more fragmented upbringing where children grow without the warmth of a shared neighbourhood. Women’s dignity, once safeguarded by the alertness of other women, is now too often left unprotected. Poverty, once cushioned by community support, turns into humiliation in an increasingly individualistic society.

We have not only lost customs—we have lost the soul that animated them. The traditions that gave Shehr-e-Khaas its moral strength now survive mostly in fading memories, in the wistful accounts of elders whose voices tremble as they recall a time when togetherness was life’s greatest wealth.

Material comforts have multiplied, but hearts have shrunk. Larger homes shelter lonelier people. Streets, once vibrant with shared life, now resemble passageways for strangers. Every bond that breaks is more than a personal loss; it is a wound to our collective identity, our history, our very soul.

Perhaps the memory of those golden days still carries within it a lesson. If recalled with sincerity, it may guide us back toward a life where hearts are bigger than homes, where neighbours are family, and where once again the lanes of Shehr-e-Khaas echo not with indifference but with laughter, greetings, and the gentle wisdom of its people.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at

Leave a Reply