Differentiating between adenomas and carcinomas is crucial for treatment. The latest diagnostic techniques and why some nodules require urgent attention.

Dr. T Vishnu Murthy

Adenomas are abnormal growths of thyroid tissue characterized by a uniform histologic pattern. These growths are typically enclosed by a capsule composed of fibrous tissue or compressed normal thyroid cells. They may manifest as solitary nodules within an otherwise normal thyroid gland, or, in less common cases, as two or three distinct adenomas. Additionally, they can be a feature of multinodular goiter, a condition where multiple nodules develop within the thyroid gland.

The most frequently encountered type of thyroid adenoma is the follicular adenoma. This variety is composed of large colloid-filled follicles lined with flattened cuboidal epithelial cells. A specific subtype of follicular adenoma, known as the “colloid nodule,” is characterized by large colloid-filled follicles and an ill-defined capsule. However, there is ongoing debate among medical professionals regarding whether colloid nodules should be classified as true adenomas.

Over time, some adenomas may undergo degenerative changes, leading to cystic transformation filled with gelatinous material. Signs of old or recent hemorrhages within these degenerating adenomas are commonly observed. Certain adenomas closely resemble normal thyroid tissue on histologic examination. Those with smaller follicles and increased cellularity are classified as fetal or embryonal adenomas. Some of these adenomas represent transitional forms between benign adenomatous growths and malignant carcinomatous lesions.

A distinct variant, known as the Hürthle cell adenoma, consists of eosinophilic cells that resemble hepatocytes (liver cells). All of these subtypes fall under the broad category of follicular adenomas. Papillary “adenomas,” another classification, are distinguished by characteristic fronds of cells that project into sparsely filled lumina. However, many of these tumors may actually be carcinomas rather than benign adenomas.

Differentiating Benign and Malignant Thyroid Nodules

One of the primary challenges in thyroid pathology is distinguishing benign adenomas from malignant thyroid cancer. In the majority of patients, a thyroid nodule is the only clinical finding, and the surrounding thyroid tissue remains normal. Most individuals with thyroid nodules are euthyroid, meaning their thyroid hormone levels are within the normal range. However, a subset of patients may present with hyperthyroidism (thyrotoxicosis).

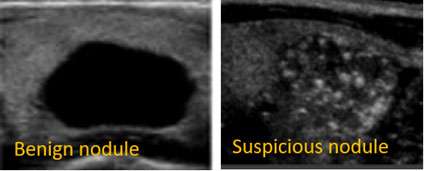

Radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) and thyroid scanning techniques are often employed to assess these nodules. In most cases, adenomas appear as “cold” nodules, meaning they do not take up radioactive iodine. However, some nodules exhibit iodine uptake equivalent to normal thyroid tissue, while others selectively concentrate radioactive iodine, classifying them as “hot” nodules. Some of these “hot” nodules may autonomously produce excessive thyroid hormone, leading to suppression of normal thyroid tissue function and, in some cases, clinical hyperthyroidism.

Thyroid nodules that are firm, fixed to adjacent structures such as the trachea, irregular in contour, growing rapidly, or associated with palpable cervical lymph nodes raise suspicion for malignancy. However, neither clinical examination nor isotope scanning alone can definitively differentiate between benign and malignant nodules. Notably, approximately 3% to 10% of thyroid carcinomas may appear as “hot” or “warm” nodules on imaging. Solitary nodules in children and men warrant particular caution, as they are more likely to be malignant.

Traditionally, thyroid nodules were treated with long-term thyroid hormone therapy in an attempt to shrink the growth. However, this approach is now considered ineffective in most cases. Instead, short-term thyroid hormone therapy before surgery may be beneficial as it helps delineate the lesion, facilitating a more precise surgical resection.

Cystic Thyroid Nodules and Evolving Diagnostic Techniques

A significant proportion of thyroid nodules, estimated to be around one-third, are primarily cystic in nature. These cystic nodules can sometimes be identified through palpation or ultrasound imaging (echograms). Some surgeons have begun treating cystic thyroid lesions with aspiration, which has shown promise in reducing the size of these nodules. Additionally, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is increasingly being used as a diagnostic tool to determine whether a nodule is benign or malignant. While concerns exist regarding potential tumor spread and the possibility of false-negative results, these evolving techniques may ultimately transform the traditional indications for surgical intervention.

THYROID CARCINOMAS

Papillary Carcinoma

Accounting for nearly 80% of all thyroid malignancies, papillary carcinoma is the most common form of thyroid cancer. These tumors exhibit fronds of cellular tissue that project into slit-like lumina containing little or no colloid. Some regions of the tumor may display differentiation into a more normal follicular structure. Papillary carcinomas are frequently microscopic and are often discovered incidentally in thyroid glands removed for unrelated reasons.

Papillary tumors tend to metastasize early to regional lymph nodes in the neck, sometimes before the primary tumor is detectable through clinical examination or imaging studies. Although they can remain confined to the cervical lymph nodes for extended periods, they may eventually invade local structures such as the strap muscles and larynx or metastasize to the lungs. The histologic characteristics of primary tumors and their metastatic lesions may differ significantly, with follicular elements sometimes present in either site.

Growth of papillary carcinoma is partially influenced by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and prognosis is generally more favorable in patients younger than 40 years old. With appropriate treatment, ten-year survival rates range between 80% and 90%. Many papillary thyroid tumors exhibit mixed papillary and follicular histologic patterns, making classification difficult. These mixed tumors behave similarly to pure papillary carcinomas, and discrepancies between primary and metastatic tumor architecture are common.

Follicular Carcinoma

Follicular thyroid carcinoma exhibits a wide range of histologic appearances, from relatively normal-looking thyroid tissue to microfollicular and solid, anaplastic-appearing tumors. Hürthle cell changes are often present. Unlike papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma spreads primarily through the bloodstream, leading to early metastasis in the lungs and bones. These tumors are responsive to TSH and frequently uptake and metabolize iodine, producing thyroid hormone. In rare cases, excessive hormone production by the tumor may result in clinical hyperthyroidism. The ten-year survival rate for follicular carcinoma is approximately 50%. Hürthle cell carcinoma behaves similarly but tends to invade and metastasize locally within the neck.

Medullary Carcinoma

Medullary thyroid carcinoma arises from the parafollicular “C” cells, which secrete calcitonin. These tumors typically form sheets of cells with large nuclei and are often associated with amyloid deposition, fibrosis, and lymphocyte infiltration. Medullary carcinoma frequently metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, the lungs, and other soft tissues. Unlike differentiated thyroid carcinomas, it does not respond to TSH. This malignancy is linked to hereditary endocrine syndromes, including pheochromocytoma and multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. Measurement of serum calcitonin can aid in early diagnosis.

Anaplastic Carcinoma

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies, with histologic variations ranging from small cell tumors to giant cell and epidermoid tumors. These tumors exhibit rapid local invasion and poor prognosis, with survival rates below 20% at one year. Treatment typically involves surgical resection, followed by radiation therapy and thyroid hormone suppression.

Treatment Strategies

The approach to thyroid cancer treatment depends on tumor type, stage, and metastatic spread. Surgical options range from lobectomy for localized lesions to total thyroidectomy for aggressive or multifocal disease. Postoperative management includes thyroid hormone suppression therapy to inhibit TSH-dependent tumor growth. In advanced cases, radioactive iodine therapy, external beam radiation, and targeted therapies may be considered.

Emerging Ayurvedic research suggests that certain herbal treatments may be beneficial in early-stage thyroid cancer, including cases with distant metastases. However, further clinical validation is necessary before integrating these treatments into standard oncologic practice.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of this Magazine. The author can be reached at Mobile: 9650696351

Leave a Reply